|

CIVILIZATION AND CONSCIOUSNESS - PART II

The historical exploration of civilizational self-control

presented in the previous chapter provides several significant

insights, which we will now examine more closely. In this

exploration, we aim to broaden our perspective, seeking a

higher-level understanding through more abstract overviews.

Man is a story-telling animal

Firstly, it's evident that the development of self-control

in civilized human isn't solely the product of advanced

cognitive abilities like logical reasoning. There seems to be an

additional, highly effective mechanism within the modern human

brain aiding self-control: storytelling, particularly through

organized religion. Contrary to the perspectives of staunch

scientists like Dawkins, who regard religion as a detrimental

mutation, historical observations, such as the development of

the Silk Roads, reveal the essential role of Buddhism and

Christianity in facilitating crucial trade lifelines.

The Rational and the Religious Mind

Unlike animals, humans have a unique propensity for

religion. Religion appears to be an effective narrative-based

social self-control tool, rooted in our capacity for

storytelling. Yuval Noah

Harari accurately describes humans as storytelling animals.

The existence of the Silk Roads owes much to religious

narratives. The contemporary human consciousness seems to

encompass two historically conflicting brain functions: the

rational and the religious mind.

It's crucial to note that this historical perspective doesn't

necessitate actual belief in any religion. Our focus is on the

unifying and civilizing influence of organized religion, which

is a distinct matter from the existence of a deity.

FROM MEDIEVAL EXESS TO THE RATIONALITY OF ENGLIGHTENMENT

Transitioning from the Silk Roads, we encounter another

significant shift in the trajectory of civilization. This shift

originated in the Italian city-states during the 15th century

with the Renaissance, eventually evolving into the Age of

Enlightenment and shaping Western civilization.

Europe's geography, being more condensed compared to the

expansive civilization zone of the Silk Roads, allowed for a

unique blend of control systems. The vastness of the Silk Roads

region made reliable military control challenging. In contrast,

Europe's smaller geographical scale enabled the effective

combination of military and religious systems for governance and

control.

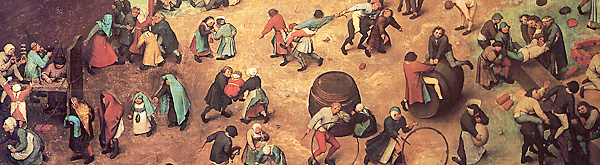

The Sensuous Middle Ages

Even in the much later period of the Middle Age, the average

person lived more spontaneously, acting on immediate sensory

experiences, at least as compared to our time. According to

Norbert

Elias this immediate,

sensory, yet unpredictable life was led without considering

potential consequences. Distress, captivity, defeat, victory,

mutilation, unrestrained pleasure, devastation, religious

penance, and remorse were experienced within the silent and

sensory space of the body. Surveillance and punishment came from

external forces like religious and secular institutions, not

from within.

Part of a painting of Bruegel

Enlightenment and Emotional Regulation

Even up to the Enlightenment, societal norms allowed behaviors

unthinkable today, like a man greeting a woman by touching her chest. People

of the pre-industrial era engaged in direct, uninhibited sensory

experiences.

Norbert

Elias's observations in "The

Civilizing Process,"

elucidate

the transition from the Medieval to the Enlightenment period

implied emotional self-control:

"The soul is

here, if one may express oneself thus without comparison, much

more prepared and accustomed to leap from one extreme to the

other with always the same intensity, and often even small

impressions are uncontrollable associations, enough to trigger

the fear and the turnaround. When the structure of human

relations changes, when monopoly organizations are formed for

corporal violence and instead of the persistent feuds and wars

the more stable urgency situations due to peaceful, money- or

prestige-acquired functions keep the individual in tight reins,

the affective expressions slowly strive towards a line in the

middle." (My emphasis)

Norbert Elias's concept of the

line in the middle is not so far from Buddha's concept of

the golden middleway as discussed in

the previous chapter.

Norbert Elias highlights that as

we progressed in the process of civilization, we transformed

from beings reliant on close-range senses to those predominantly

guided by long-range, visual perceptions. In this evolution, the

term "Enlightenment" carries a significant implication

as a visual sense.

Emotional regulation became crucial, and our sensory experiences

shifted from direct tactile engagements to more distant

observations. This transformation is encapsulated in the term

"Enlightenment," which defines the post-medieval "Age of

Reason." For 17th-century thinkers, "the

Golden Middle Way" emerged as a paramount self-control concept, which can

be seen as history echoing itself.

This is precisely why I chose to take a brief detour from the

Silk Road to later European history.

Throughout the

history of civilization, dating back to pre-medieval times, our

evolution has been characterized by a shift towards becoming

more composed individuals in more harmonious settings.

Consciousness, as the most recently evolved operational system,

finds it challenging to manage intense emotional disruptions,

which can be viewed as remnants of older, more primitive

animalistic systems. Given its recent evolutionary emergence,

consciousness is inherently fragile and prone to regression. As

such, fostering self-control is crucial for the development and

maintenance of conscious awareness which again is a foundation

for higher organized civil life.

In this context, when we examine Buddhism and Christianity, we

find a common focus on maintaining control over the higher

mental faculties always threathened by animal nature. Buddha faced his battles against Mara and

various demons. Jesus contended with the devil in the

wilderness. Monks from both traditions strive to overcome their

desires and the more base aspects of their minds.

From this perspective, modern new age religions appear to be

engaged in the inverse task: liberating our senses from the

burdens of excessive civilization. This aligns more with Greek

and Roman religions, where figures like Dionysus symbolized a

more hedonistic approach and held a place among the gods.

To Winn is to Loose

This reversed role of

modern religious sentiments highlights the success of organized

religion in civilizing humanity to the extent that it created

environments conducive to the flourishing of consciousness.

In Zen religion there is a saying: To winn is to loose. Christian institutions were so effective in this regard that

they eventually made their own role in maintaining societies

via religious sentiment redundant.

The French Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire famously remarked,

"There is no God, but don't tell that to my servant, lest he

murder me at night." This statement captures the essence of

a time when, despite the declining influence of religion among

the educated classes, it remained a vital moral and social

anchor for the masses. Voltaire outlived the strict religious

observance of his servant, symbolizing the enduring impact of

religious belief even as it waned in the Enlightenment era. In

this period, the notion of acting morally and maintaining order

increasingly became seen as rational and self-evident,

independent of divine decree.

The embedded embodiment of the story of goodness

The original teachings of Buddhism on the Silk Road eventually

evolved into Christianity. Christianity itself then transformed

into a largely unspoken, but deeply ingrained memory of good

conduct within societal structures. This code of behavior,

embedded in the body, paved the way for an enlightened state

transitioning towards secularism. By this stage, religious

reminders to be virtuous were no longer necessary. The social

ethos of good conduct had become a silent yet potent force,

resonating from person to person, beyond the realm of language.

A significant shift in this process occurred in Northern Europe with the

Reformation, allowing state power to integrate with religious

institutions. It's important to recognize that most of societal

information is non-verbal. This includes a range of

communications from body language to emotions, which are

transmitted in societies, often unnoticed by a Western mindset

overly focused on linguistics and often oblivious to non-verbal

forms of information.

The evolution of state-building where religious institutions

have become integrated into the societal subconscious is

particularly evident in the social democratic models of

Scandinavia. In my country, Denmark, deep religious beliefs are

far less common than they were in my grandparents' generation.

Yet, there persists a general trend of people behaving kindly

towards one another. This can be seen in the context of a social

system where the state, providing comprehensive social security

for all citizens, has emerged as a kind of anonymous embodiment

of the Good Samaritan.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's assertion in "Tractatus

Logico-Philosophicus" (1922), "The limits of my language mean

the limits of my world," appears somewhat deceptive when

considering the extensive, unspoken social currents of

behavioral information. While Wittgenstein acknowledges the

existence of phenomena beyond language, he advises silence on

such matters. It's puzzling why he suggests this restraint. Why

should we remain silent about what lies beyond the realm of

language? This aspect of his philosophy is challenging to

comprehend. I dare to disagree and align with Whitehead:

An enormous part of our mature experience

cannot be expressed in words.

Alfred North Whitehead

Language-centric perspectives on human interaction and societal

norms often overlook the zoological aspects inherent in us,

aspects that have journeyed through time like a starship teeming

with various inhabitants such as viruses, bacteria,

mitochondria, and a multitude of cellular formations. A common

denominator unifies all these biological operative systems:

their ability to communicate without relying on language.

THE EMERGENCE OF NON-DUAL CONSCIOUSESS

It is now time to elevate our discussion to consider consciousness as

an abstract, shared field that unites humans at various levels,

ranging from individuals to clans, tribes, nations, and beyond.

For a deeper understanding of this concept, I recommend reading

the chapter titled "Shared

Fields of Consciousness"

before proceeding further.

Let's return to the Silk Roads to explore the emergence of

non-dual consciousness. The link between the expansion of trade

networks and the development and configuration of consciousness

is intrinsically intertwined. Simply put, the concept of unity

consciousness, which grew alongside urban development and the

prosperity brought by long-distance trade, is simultaneously a

fundamental necessity for the survival and thriving of these

very developments.

Cognitive consciousness inherently functions within the duality

of subject and object, the knower and the known. Similarly,

tribal consciousness operates in a duality, consistently

differentiating 'us' from 'them.' Religion has often reinforced

this tribal dualism by categorizing people into believers and

non-believers.

Both the shamanistic hunter-gatherer and the later

agricultural-based cultures were

fundamentally based on and in a dual consciousness and the split

understanding of reality made by of the same.

Buddhism, however, presented a completely new transformative

approach. Through the cultivation of consciousness in its

essential form, it transcends these almost biologically

inherited tribal divisions.

There are many ways of understanding non-duality.

In this context, by non-duality, I am referring to a state where

Buddhist 'shunyata', or emptiness, encompasses everything,

particularly recognizing all living beings as part of a unified

whole. Here non-duality takes us from the understanding of that

there is no 'other', to the understanding that I am everybody

else.

This inclusive acceptance was crucial not just for the

long trade routes crossing diverse regions with different

cultures and languages, but also for the emerging urban life on

the Gangetic plains and in the series of Greek cities from

Greece to India. A feudal or tribal mindset, less suited to life

in populous cities, necessitates the coexistence of people from

varied backgrounds and beliefs. Here, Buddhism addressed a

societal need, aligning with the principle of 'follow the

money'. It presents Buddhism as a socially adaptive force

promoting harmonious coexistence in diverse environments. To put

it succinctly: Buddhism, perhaps alongside Jainism, extended

compassion not only within its group of adherents. Its concept

of 'metta' (loving-kindness) embraces everyone, regardless of

caste, creed, or culture, in a spirit of universal oneness. This

represents a significant breakthrough in civilizational

development.

Christianity eventually embarked on a similar journey. However,

this path paradoxically coincided with relentless religious

conflicts, either among different Christian sects or against

Islam. However, the Christian mystics kept this

My favorite Mantra: What the Fred knows Fuck about

Consciousness

How can we look at this from the level of higher

understandings of consciousness? Let me first of all repeat my

mantra that we fundamentally do not know what consciousness is.

In order to understand consciousness we should be on a higher

level as consciousness itself, what we will never be, at least

in the understanding that consciousness is a guest, an intruder

from a higher dimensiona plain.

Consciousness is a cat from another dimension. However, it

is possible to look at some of the 'lower' aspects of

consciousness, like described in the anology af the

footsteps of the invisible thief.

When considering consciousness

from a more elevated perspective, it's imperative to acknowledge

a fundamental uncertainty: we don't truly understand what

consciousness is. To fully grasp consciousness, we would need to

be on a level higher than consciousness itself, which seems

unattainable, especially if we consider consciousness as an

entity or phenomenon originating from a higher dimensional plane

– akin to

a cat from another dimension.. Nonetheless, we can examine

some of the more accessible aspects of consciousness, as

illustrated in the analogy of tracking the

footsteps of the invisible thief.

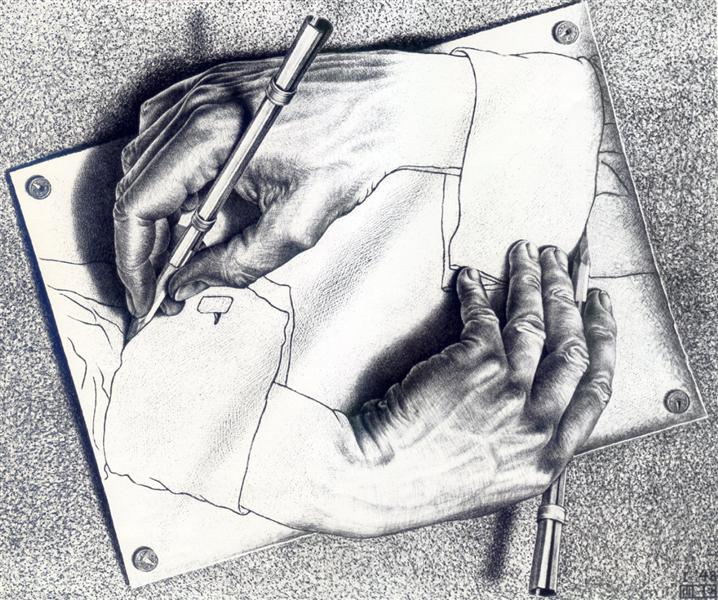

Consciousness mirrored in complex feedback system

Consciousness, as I intuit through deep meditation, is

mirrored in biological

multifaceted and complex information systems, possessing profound

feedback capabilities. The complexity and efficiency of this

system, even from a Darwinian perspective, correlate with the

expansion of consciousness in both quantity and quality. Viewed

in this light, consciousness involves the interconnection of

neurons linking various parts of the brain, similar to how the

Silk Roads served as cultural conduits. Consequently,

consciousness had to broaden, akin to an expansive embrace, to

cover the immense geographical stretch from India to Europe.

Rings of Power

The first layer of

consciousness is focused on individual survival, which is why we

refer to parts of our body as 'my arm' or 'my leg'. The next

layer extends to encompass our immediate environment, including

'my things', 'my land', and most importantly, 'my loved ones'.

Our consciousness, in this regard, expands in relation to what

we identify with as 'mine'. Anything perceived as not 'me' or

'mine' is often viewed as a potential survival threat. The

subsequent layer is the tribal one, which in the era of social

media has evolved beyond a physical clan striving for collective

survival, transforming into a community of souls connected in

their chosen digital rabbit-realms.

At its more basic levels, this tribal consciousness is often

governed by a 'Gollum-mentality', focused on possession and

self-interest. It's only when this consciousness transcends

itself, dissolving into nothingness and thereby encompassing

everything, that we can truly embrace others. This is

exemplified by strangers on the Silk Road greeting each other

with a respectful 'pranam', recognizing the underlying

oneness and shared emptiness that connects us all.

Ashoka-Buddhism represents the first organized religion to

achieve a breakthrough into true non-duality, and I make this

assertion without being a Buddhist myself.

However, I discern echoes of Buddha's concept of emptiness in

the double negations of my favorite mystic, Meister Eckhart.

Listen here to what the Meister has to say:

"Things are all made from nothing;

hence their true source is nothing."

I could continue drawing parallels

between Vedanta, Buddhism, and the teachings of Meister Eckhart.

However, this is not the appropriate forum for an extensive

comparison, so I will limit myself to a quote that aligns the

Indian concept of

'Neti, neti' –

not this, not that – with one of Eckhart's many similar

assertions:

"God is such that we apprehend him better by negation than by affirmation."

The following quote aptly

delineates the distinction between consciousness, confined by

the denial of being the other, and God, or consciousness as

omnipresent in all and nothing:

"All

creatures contain one reflection:

one, that is the denial of its being

the other;

the highest of the angels denies he is the lowest.

God is the denial of denials."

Doctor Ecstaticus/ Meister Eckhart

The Meister and

Luhmann

Meister Eckhart also asserts:

"The tendency is ever towards self-repetition,

towards the preservation of

the species:

it is every man' s intention that his work should be himself."

Meister Eckhart

This statement brings to mind the in-depth systemic theories of

Niklas

Luhmann. In this context, I suggest incorporating

consciousness as a crucial, albeit unseen, orchestrator of

social systems, driven by their inherent intention to replicate

themselves.

The Silent Systemic Power of Consciousness

The concentric circles of consciousness are shared

information fields that, as previously mentioned, transcend

language. In a sense, they also transcend the host, the body

itself.

At this juncture, we venture into realms less charted by

science, into territories closer to the unknown. I am reminded

of Bertrand Russell's analogy of the celestial teapot; if I

assert that a teapot orbits the Earth, brimming with hot,

delicious tea, it's not the responsibility of science to refute

this claim, but mine to substantiate it.

Nonetheless, driven by my intuition, I am drawn to delve into

this concept, fully acknowledging that this exploration

resonates more with shamanic guidance than with scientific

validation. Despite my appreciation for empirical and historical

analysis, I do not confine myself to the traditional academic

boundaries. I choose not to think and write within these

systemic limits, which, in my view, often hinder truly

innovative thinking in favor of a 'better safe than sorry'

approach, constrained by the practicalities of everyday

responsibilities like monthly mortgage payments.

The Power of the Silent Field

The potency of shared fields of consciousness extends beyond

the realm of Yuval Noah Harari's concept of the 'story-telling

animal'.

I have personally experienced this phenomenon in various

settings, notably in group meditation. Similarly, in the gym,

the collective energy and motivation enable me to lift weights

that would be challenging to handle alone at home. This

phenomenon is also evident in social media communities, where

individuals converge around common interests or beliefs. From

the compelling oratory of figures like Hitler to large rock

concerts, and even among the numerous 'fake Gurus' that Sufi

mystic

Shams of Tabrizi likened to the countless stars in the sky, there is

an observable innate human yearning to surrender to something

larger than oneself.

But how does this happen? It occurs through our sensory

perception of body movements, even at a micro-level. We often

subconsciously mirror the bodily expressions of those we

identify with, leading to a synchronization similar to soldiers

marching in unison.

Yet, there are additional forces at play. Social media, in its

disembodied form, has shown how powerful fields of consciousness

can emerge without physical imitation. My theory, which remains

unsubstantiated, posits that this social cohesion, the temporary

ecstasy of surrender, is not solely a result of storytelling or

bodily synchronization. It seems to be an inherent quality of

consciousness itself.

In my many experiences with group meditation, where participants

sit silently with closed eyes, the presence of a profound

collective spirit – which could be likened to the 'holy ghost' –

is occasionally tangible, and at other times, it is not. This

presence seems not to be tied to any particular set of

conditions, apart from, perhaps, the purity of the hearts of

those present. When this spirit is present, there is a shared,

instantaneous recognition among everyone that everyone is aware

of its presence.

This phenomenon I perceive as the cosmic glue is best described

as love. However, this love must continually transcend itself

into larger circles of consciousness to foster the creation of

greater civilizations. Otherwise, it risks imploding under the

sheer force of its own boundaries, constrained by defining

itself against what lies outside.

Consciousness and Civilization

|