|

|

CIVILIZATION AND CONSCIOUSNESS - PART I

Buddhism and Christianity seen as Civilizational Self-control

Zones

In this exploration, we delve into how historical societal

developments have laid the groundwork for enhanced living

conditions, thereby nurturing the growth of consciousness. As

previously discussed in our

chapter on

Consciousness, while the core nature of consciousness

remains largely enigmatic, we understand that aspects like

language-based cognition and the development of analytical

reasoning are central to its operation. These facets of

consciousness have been primarily cultivated within the

nurturing environments of religious institutions.

As we proceed, we will focus more closely on consciousness,

considering it as the pinnacle of humanity's neural evolution.

This advanced aspect of our neural architecture, being a recent

evolutionary development, is also our most fragile. In times of

stress, this delicate flame of consciousness can be easily

threatened. Therefore, the progress of civilization can be

likened to a series of architectural projects, constructing

systems of self-regulation that support and allow this nascent

bio-cognitive function to thrive.

On the cusp of analogy, one might contend that an intricate

network of communication and trade, as established by

civilization, reflects a more sophisticated network of neurons

within the brain. There is a tandem progression between

civilization and consciousness, each evolving and becoming more

complex in concert.

The inception of civilization saw

us evolve from beings predominantly governed by raw

instinctual awareness

to those more in tune with

consciousness. In the ensuing sections, I will adopt a

materialist-historical lens to delve into consciousness. While I

don't strictly adhere to materialism as a philosophical

standpoint, I regard it as one of the many potent tools for

comprehension.

Starting our exploration from the ice age might be tempting, but

given the sparse and often inconsistent data from that era, our

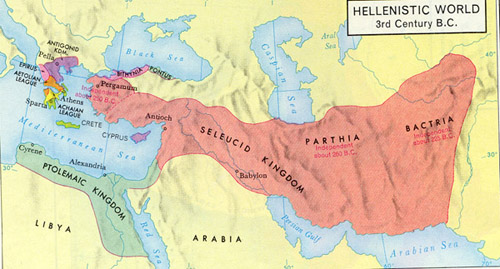

journey will commence with closer look at the trade routes

beginning at the time of the conquests of Alexander the Great.

In this context it's crucial to acknowledge that during these

times, a staggering 60% of the world's population made their

homes along these trade conduits from the Far East to the Middle

East.

My goal is to illustrate the interplay between consciousness and

civilization: how consciousness contributes to the building of

civilization, and conversely, how civilization fosters the

development of consciousness. Simultaneously, we must consider

religions and religious institutions as prime environments for

nurturing the growth of consciousness. In this exploration,

personal belief in religion is irrelevant. Even a

fictional narrative can unite us in shared realms of abstract

consciousness, demonstrating how collective beliefs, whether

factual or fictional, are able to create

a shared field of

consciousness.

CIVILIZATION AND THE BIRTH OF

NON DUAL CONSCIOUSNESS

The Pivotal Role of Silk Routes in the Confluence of

Civilizations and Consciousness

In the crucible of interaction between East and West, both

cultures underwent irrevocable transformations that have left an

indelible impact on our world. While it might seem like a

digression to delve deeply into the unfolding of civilization in

the attempt to understand the unfoldment of human consciousness,

this significant facet of history anyhow warrants closer

attention.

The advent of human civilization and consciousness

was propelled dramatically forward with the establishment of the Silk Roads,

famously known for bridging China with Europe. Yet, the earlier trade networks

that connected India, the Middle East, and Southern Europe are often not given

due recognition. As highlighted by Giovanni Veradi, the significance of

North-western India in the realm of Buddhist and Indian studies has been largely

underestimated:

"North-western India enjoys, or rather suffers

from,

a peculiar situation in the field of Buddhist and Indian studies."

'Buddhism in North-western India and

Eastern Afghanistan'

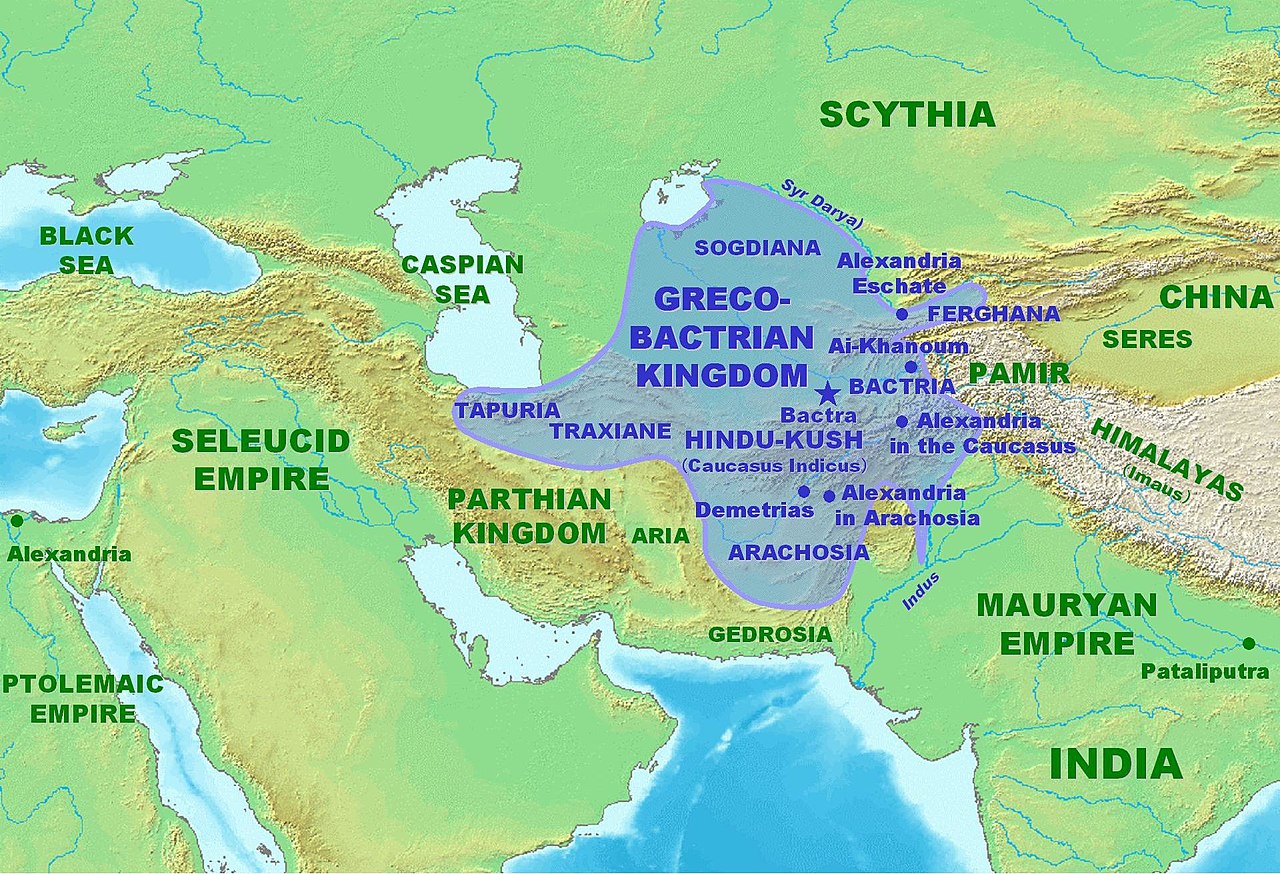

I would venture to broaden Veradi's insight to

encompass not only religious aspects but also cultural and commercial exchanges.

Similarly, its neighbor, the

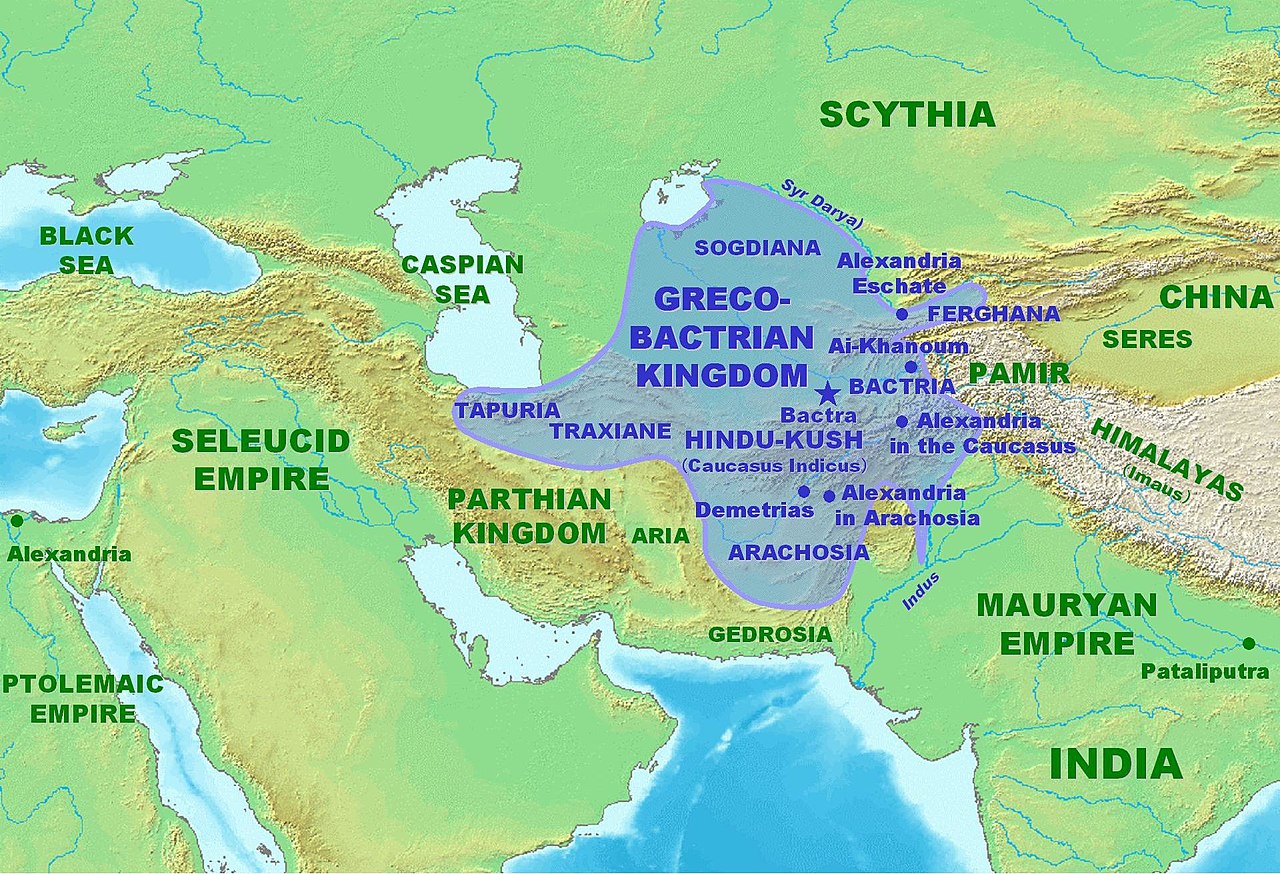

Greco-Bactrian

Kingdom, was one of the wealthiest and most influential states at its peak.

This is reflected in the title of H.G. Rawlinson's work: "Bactria, The

History of a Forgotten Empire".

In this section, I will focus my analysis on the vibrant 'trade synapses' that

linked India with the Western world, deliberately omitting China from this

discussion.

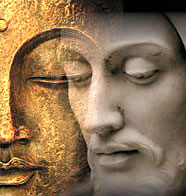

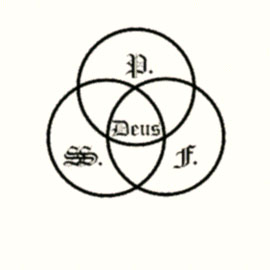

Borromean rings

of Unity

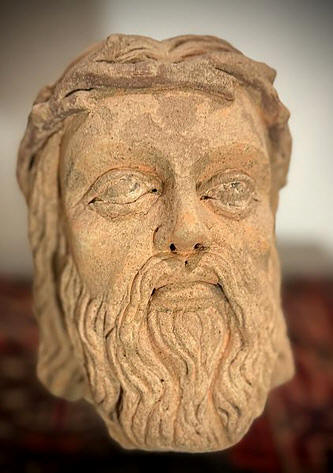

To offer a glimpse into the

forthcoming discussion let's contemplate the Borromean rings—a

symbol of interconnectedness. The sculpture on the left

illustrates the Buddhist Triple Gem: the Buddha, the Sangha, and

the Dharma, known as the TRi-RaTNaS in Sanskrit. In parallel,

the image on the right represents the Christian Holy Trinity,

termed TRi-NiTaS in Latin. These symbols, though from distinct

traditions, both convey a unity that transcends individual

elements, hinting at the profound interrelation between

civilization and consciousness we are set to explore.

Buddhism and Christianity in Mutual Co-creation

It's impossible to envision Buddhism as we know it without

acknowledging the influences of Greek thought, just as we can't fully understand

the foundations of Christianity without considering its debts to Buddhist

philosophy. As Max Müller states in "India: What It Can Teach Us," there

are striking resemblances between Buddhism and Christianity that are impossible

to ignore, particularly given that Buddhism predates Christianity by at least

four centuries. He encourages scholarly exploration to uncover the historical

channels through which Buddhism might have influenced Christian thought:

That there are startling

coincidences between Buddhism and Christianity cannot be denied,

and it must likewise be admitted that Buddhism existed at least

400 years before Christianity. I go even further, and should

feel extremely grateful if anybody would point out to me the

historical channels through which Buddhism had influenced

Christianity.

India: What it can teach us - Max Müller

In a similar vein, the statement

from Draaper's "Intellectual Development of Europe" also

acknowledges that if European ideas made their way to the far

East via the Bactrian Empire, then it's also likely that Asiatic

ideas, in turn, seeped into European consciousness through

similar channels.

If through the Bactrian Empire

European ideas were transmitted to the far East, through that

and similar channels Asiatic ideas found their way to Europe.

Draaper: Intellectual Development of Europe, I. ii.

Elaine Pagels, a British scholar of Buddhism, observes:

"Yet the gnostic Gospel of Thomas relates that as soon as Thomas

recognizes him, Jesus says to Thomas that they have both

received their being from the same source... Does not such

teaching—the identity of the divine and human, the concern with

illusion and enlightenment, the founder who is presented not as

Lord, but as spiritual guide—sound more Eastern than Western?

Some scholars have suggested that if the names were changed, the

'living Buddha' appropriately could say what the Gospel of

Thomas attributes to the living Jesus. Could Hindu or Buddhist

tradition have influenced gnosticism?... Trade routes between

the Greco-Roman world and the Far East were opening up at the

time when gnosticism flourished (AD 80–200); for generations,

Buddhist missionaries had been proselytizing in Alexandria. We

note, too, that Hippolytus, who was a Greek-speaking Christian

in Rome (c. 225), knows of the Indian Brahmins, and includes

their tradition among the sources of heresy..."

This quote provides an insightful perspective on the

similarities between certain aspects of Buddhist and Christian

teachings, suggesting a potential historical connection through

trade routes and cultural exchanges.

THE SILK ROAD AND OCRAM'S RAZOR

Despite the paucity of direct evidence conclusively

establishing Christianity as a Western adaptation of Buddhist

principles, the hypothesis merits further investigation. This

inquiry, guided by the principles of Occam's Razor, aims to

navigate through the complex web of historical, philosophical,

and cultural contexts. By applying this analytical tool, which

favors simpler explanations over more complex ones, we can

explore whether the paths of these two great religious

traditions might have intersected in a meaningful way.

Our exploration will concentrate on circumstantial evidence,

such as the historical timelines of Buddhism and early

Christianity, and the extensive network of trade routes like the

Silk Road, which facilitated rich cultural

exchanges between the East and West. This approach will

allow us to consider the possibility of ideological and

philosophical transmissions between these two regions.

Furthermore, we will delve into the intriguing parallels between

Buddhist and Christian teachings. This comparative analysis will

focus on similar ethical teachings, motifs in parables, and the

overarching philosophies present in both religions. Such

parallels, while not definitive proof of direct influence, can

provide insights into the shared human experiences and universal

truths that these religions encapsulate.

Interpretative analysis will also play a crucial role in this

exploration. We will examine how religious ideas and practices

often evolve by incorporating elements from existing beliefs and

how these adaptations are understood by various scholars and

historians. This will include a consideration of the syncretic

nature of religious development and the challenges in tracing

the origins of specific doctrines or practices.

It is important to note that while this investigation aims to

present persuasive arguments for Buddhist influences on

Christianity, it inherently recognizes the speculative nature of

such a thesis.

SPICE TRADE AND RELIGION

Since the era of Alexander the Great, a vibrant spice trade

has flourished between the Greeks and India,

symbolizing a broader exchange far beyond mere commodities. The

Silk Road, renowned for its commercial significance, functioned

as a dynamic conduit for the exchange of ideas and cultural

practices, potentially extending to the philosophical and

spiritual concepts that influenced early Christianity. The

impact of this trade is metaphorically akin to the Roman

culinary adaptation of Indian spices. The Roman Empire's spice

trade with India began following the conquest of Egypt by

Augustus in 30 BCE. This conquest opened up new trade routes and

opportunities, significantly impacting the scope and nature of

the spice trade between these two regions. The introduction of these

exotic flavors didn't lead to the Romans directly replicating

Indian cuisine; rather, it inspired a transformative fusion

within their own culinary traditions, creating something

uniquely new while retaining a Roman essence.

This analogy serves as a potent metaphor for the potential

cross-pollination of religious ideas. Just as spices subtly yet

significantly altered Roman cuisine, it is plausible to suggest

that the religious and philosophical ideas traveling along these

trade routes might have similarly 'spiced up' the religious and

cultural life in the Western reaches of these networks.

Buddhism, which had already established a wide presence in Asia

by the time of these exchanges, could have feasibly left subtle

imprints on the evolving religious thoughts in the West.

Thus, in this context, the suggestion that emerging Western

religious thought, particularly early Christianity, could have

been influenced by Eastern philosophies like Buddhism becomes a

compelling hypothesis. It proposes a scenario where the essence

of Christianity is preserved, yet it is enriched and subtly

transformed by the infusion of ideas and concepts borne along

the Silk Road, mirroring the culinary metamorphosis induced by

the spice trade.

Buddhism's Influence on Christianity: Subtle and Overlooked

The subtle impact of Buddhism on Christianity is partly due

to Buddhism's understated, decentralized spread. Its peaceful

dissemination, focused on universal moral teachings rather than

charismatic leaders, is less apparent in historical records

compared to the more overt conversion efforts of later Christian

and Islamic missions. This makes Buddhism's influence on other

religions, including Christianity, more elusive and difficult to

document.

THE FOLCLORIC SPREAD OF THE JATAKA TALES

As dusk fell upon the caravanserais connecting the East with

the West, the glow of firelight became the backdrop for

storytelling. Since the time of the Buddha, oral folkloric

spread tales evolved on the Gangetic plains. These tales are

today known as the

As twilight descended on the

caravanserais bridging East and West, the flicker of firelight

set the stage for storytelling. These tales, originating from

the Buddha's era on the Gangetic plains, are known today as the

Jataka

tales. Laden with moral teachings, they provided more than

just entertainment for travelers; they spread Buddhism's ethical

principles. This dissemination wasn't just of religious doctrine

but a universal ethos of kindness and morality, adaptable across

various cultures. The Jataka tales' universal themes of ethical

behavior resonated deeply along the Silk Road, interweaving into

diverse spiritual traditions and nurturing a rich cultural

exchange.

The Jataka tales, a cornerstone of

oral tradition, linked distant civilizations, traveling with

caravans from India to Persia and even to Scandinavia. In

Denmark, for instance, the Molbo tales, according to prefatory

notes in collections of these stories, are believed to have

roots in the Jataka narratives. While specific cultural elements

like caste distinctions didn't transfer to Danish versions, the

core storytelling principles endured. The

Danish

Molbo tales adapt these narratives, replacing the 'ignorant'

Brahmins with 'naive' Molboes, preserving the Jataka's original

narrative structures. This adaptation maintains the satirical

humor intended to evoke laughter, demonstrating how the core

structure and purpose of the Jataka tales have been retained and

localized in Danish folklore.

Holberg's "Jeppe on

the Hill": A Tale of Two

Interpretations

From oral traditions these wandering tales made their way

into litterature and drama. The Danish author and enlightenment

philosopher,

Ludvig Holberg's "Jeppe on the Mountain" serves as an

especially interesting example of cultural adaptation. According

to Kaare

Foss in "Konge for en dag" ("King for a Day"),

Ludvig Holberg's "Jeppe på Bjerget" ("Jeppe

of the Hill") serves as example of how stories adapt and

evolve across cultures and epochs. In Holberg's rendition,

Jeppe, a poor and humble man, awakens to find himself in the

luxurious circumstances of a baron. This story traces its

lineage back through various European adaptations to "One

Thousand and One Nights," a collection with Persian origins.

Even further back, the narrative can be traced to Indian Jataka

tales where the protagonist, usually a poor man, wakes up in a

palace, suddenly a maharaja (king).

The original Indian version focuses on the moral theme of

"maya," or illusion. It poses a question: are you a beggar

dreaming you're a king, or a king dreaming you're a beggar? This

foundational concept is, interestingly, lost in the earliest

European adaptations. These versions more reflect the nobility's

disdain for the aspirations of the lower classesrather than the

philosophical concept of illusion.

The moral in Holberg's unique adaptation, centers on the dangers

of role-swapping and the inadequacies of a commoner

impersonating a nobleman. Thus, the same story reflects

different cultural values and concerns when it travels.

A Complex Web of Narratives

Even

Hans Christian Andersen's famous tale "The

Emperor's New Clothes" echoes this ancient exchange. Its

moral lesson about a child's innocence piercing through social

pretense finds its parallel in Indian traditions of wearing very

fine silk, so fine that it is almost invisible.

The Emperor's New Clothes has long been cited as a

classic fable cautioning against vanity and the unwillingness to

face uncomfortable truths. In this story, the emperor, swayed by

his own vanity and the cunning of his advisors, parades naked in

the belief that he is wearing "invisible" clothes visible only

to the wise and competent.

While this story often is read as a unique product of European

folklore, it shares intriguing parallels with older traditions

traceable to the Silk Road's influence. One such connection lies

in the material said to be used for the emperor's "new clothes"

— a fabric so fine and luxurious that it appears invisible. This

aspect of the tale have roots in ancient Indian traditions

around silk clothing.

In Buddhist iconography, religious figures are sometimes

depicted wearing extremely fine silk, so delicate that it

renders them almost unclothed. This portrayal, where their forms

are subtly draped, implies that the fabric's fineness is a

symbol of spiritual significance. The concept of "shunyata" or

spiritual emptiness is mirrored in these almost non-existent

garments, creating a paradox where a dress so valuable

essentially becomes invisible, symbolizing kingly renunciation.

This juxtaposition of opposites — value and non-existence —

serves as a metaphor for spiritual enlightenment and

renunciation in Buddhist thought.

This intriguing paradox resonates through history, including

into the Mughal period. For instance, Emperor Akbar once

reproached his daughter for appearing naked before him. Her

response revealed a subtle cultural nuance: she was actually

adorned in three layers of extremely fine silk. This incident

highlights the cultural and historical continuity of the value

placed on fine, almost imperceptible silk, embodying a blend of

modesty, luxury, and the nuanced perceptions of material and

appearance in different cultural contexts.

The enduring legacies and widespread influence of these cultural

constructs demonstrate the deep interconnectivity of the ancient

world. This interconnectedness is evident both historically and

geographically, revealing a rich tapestry of cultural exchanges

that transcended regional and temporal boundaries.

Jesus and Buddha: Icons in Pan-viral Storytelling

Is Christian baptism rooted in ancient river cultures? In

India, a timeless realm, millions still perform baptism-like

rituals in the Ganges at Varanasi.

Religious ideas, like water, flow through time and space,

morphing to fit the cultural terrains they traverse. Religions

and their leaders are thus adaptive reconstructions, crafted

from pre-existing elements. Figures like Jesus and Buddha emerge

from these ideological streams, embodying humanly shaped

channels of thought.

To illustrate the

transmutation of stories across cultures, consider the tale of a

clever young man from the reign of the Indian Emperor Akbar in

the 16th Century, which later became associated with the Danish

King Christian IV in the 17th Century. In the Indian narrative,

a bright youth impresses Akbar with his wit at a crossroads and

is subsequently invited to the royal palace at Fatehpur Sikri.

Upon his arrival, he is extorted by a guard demanding half of

whatever reward he receives from the emperor. Cunningly, the

young man requests 100 lashes from Akbar, who, upon

understanding the situation, admires the young man's ingenuity

and offers him a position in his ministry instead.

In Denmark, a tale echoes this pattern with King Christian IV.

He is said to have rescued a young man who fell through the ice

between Copenhagen and Malmø. In the court, an event unfolds

reminiscent of the Fatehpur Sikri story, including a guard

confiscating the young man's diamond ring and his subsequent

request for 100 lashes. Within 50 years, this narrative, perhaps

an amalgamation of the Danish king's rescue and Akbar's tale,

evolved to depict Christian IV as a generous ruler. This

illustrates how stories like that of Jesus may have similarly

evolved through such amalgamations.

ACADEMIC EUROCENTRISM IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES

In the scholarly investigation of world religions, there

seems to be a discernible hesitancy within academia to fully

explore the interplay and influence of stories and philosophies

across different cultures. Unlike the field of world literature,

where scholars like Professor Kåre Foss readily trace literary

influences from the Gangetic plains to Scandinavia, religious

studies often exhibit a contrasting approach. This field appears

less inclined to acknowledge or investigate the potential

cross-cultural fertilization of religious ideas and narratives.

The strong resistance within academic circles to theories like

those proposed by Dr. Phil Christian Lindtner, concerning the

origins of Christianity in Buddhism, may stem from a combination

of both justified scientific skepticism and less objective

factors. While Lindtner's hypotheses might be oversimplified in

their approach, the vehement opposition they encounter points to

a deeper issue within the field. This resistance suggests a

complexity in academic discourse that transcends simple

scholarly disagreement.

It is worth questioning if institutional biases and collective

pride in Western academia might lead to reluctance in

considering theories of significant Eastern influences on

Western religious thought. This resistance could contradict

Occam's Razor, favoring simpler explanations. The challenge lies

in using the lack of evidence as a reason to dismiss discussions

about Buddhist-Christian links, especially when this absence

might stem from the same unwillingness to explore these

connections.

The teachings of Buddha, who noted the human tendency to easily

recognize others' faults while overlooking one's own, find a

parallel in Jesus' metaphor of noticing the splinter in

another's eye but not the log in one’s own. This analogy raises

a critical question about the introspective capacity of Western

academia. Are scholars in the West, like their counterparts in

other parts of the world, potentially influenced by their own

cultural and emotional biases, thus hindering a more objective

understanding of religious history?

For instance, the rise of the Hindutva movement in India and its

impact on historical interpretation by Indian historians

highlights the influence of political ideologies on academic

research. This leads us to ponder whether Western academia, too,

might be unconsciously shaped by its own cultural narratives and

biases, thus affecting its openness to theories that challenge

Eurocentric views of religious development.

This trend highlights a broader issue in Western religious

scholarship: a hesitance to fully recognize external cultural

influences. This tendency to perceive Western religious

traditions as largely self-developed extends to underestimating

the profound influence of Islamic science and culture on

European thought. Such a Eurocentric perspective overlooks the

rich tapestry of intercultural exchanges that have shaped

civilizations.

"...the task of theology (in

the university) is to make us hold unto the object of

faith...Jesus Christ, (who) goes before and lies outside the

Biblical writings......" Mogens "Menschensohn" Müller,

leading Copenhagen professor of the New Testament, in Kristeligt

Dagblad, 9-5-2014 - Quoted from Jesusisbuddha.com

In this context,

it's pertinent to observe that the academic study of religion

often presents a unique intersection where science and belief

intermingle, perhaps more than is ideal. It's rare for atheists

to deeply engage in religious studies, which may indicate that

this field, striving for scientific legitimacy, often harbors

scholars with inherent religious beliefs. This duality

potentially influences their academic pursuits, unlike in fields

like chemistry, where personal beliefs are less likely to

intersect with scientific inquiry. Thus, in religious studies,

scholars may find themselves navigating between scientific

objectivity and personal faith.

This issue is crucial in

historical and religious scholarship, where researchers'

personal beliefs and cultural backgrounds could influence their

interpretations, notably in the study of links between Buddhism

and Christianity. Take, for example,

Paula

Fredriksen, a renowned historian in early Judaism and

Christianity. Originally a Catholic, she later converted to

Judaism. This aspect of her personal religious journey offers

insight into her scholarly approach, particularly if her work

reflects a denial of Eastern influences on early Christianity.

It raises questions about whether such perspectives might be

influenced by personal religious convictions.

Often, Western scholars question the link between Christianity

and Buddhism, citing fundamental doctrinal differences. However,

the interaction between

Hinduism's Advaita Vedanta and Buddhism

demonstrates that significant differences in belief systems

don't preclude mutual influence. These traditions, despite their

distinct philosophies, have influenced each other, particularly

in metaphysical and spiritual practices.

This suggests that historical and

cultural exchanges between religions or philosophies can happen

despite significant doctrinal differences. The evolution of

religious and philosophical thought often involves a complex mix

of adopting, adapting, and sometimes challenging elements from

other systems. Thus, the argument that fundamental differences

between Buddhism and Christianity negate the possibility of

influence is not necessarily definitive. Exchange and adaptation

of ideas can coexist with, or even arise because of these

differences.

The prevalent dismissal of

Buddhist influences on Jesus by Western scholars may furthermore

stem from their general lack of proficiency in Sanskrit, Pali,

and Tibetan, as well as a limited understanding of ancient Asian

cultures.

How does one

prove that something is a copy of something else? Surely, one

must have the original as well as the copy at hand. Scholars

have failed to identify Q (the primary source) simply because

they did not consider reading MSV (Mûlasarvâstivâdavinaya) and

SDP (Saddharmapundarîka)

in the original Sanskrit. It is as simple as that. -

Lindtner,

Jesusisbuddha.com

This gap in expertise suggests a

need for a more open reception to the insights of specialists

like Lindtner, who possess extensive knowledge in these areas,

from language to history. Embracing such expertise could offer a

more nuanced and comprehensive perspective on the historical

interplay between these two great religious traditions.

The Silk Roads, as a nexus of intercultural exchange, played a

crucial role in this process, facilitating a dynamic interchange

of ideas, practices, and beliefs. They contributed significantly

to our understanding of religious developments, including the

ascetic elements within Christianity. As ideas and practices

traversed cultures, they tended to evolve and amalgamate,

forming hybrid traditions rather than direct transpositions.

Occam's Razor, which posits that the simplest explanation is

often the correct one, would suggest that the extensive network

of the Silk Roads naturally facilitated the exchange and

adaptation of religious and cultural practices. It would be an

oversimplification to assume that influences between East and

West were unidirectional or that they did not significantly

impact the religious and cultural landscapes they connected.

The responsibility of scholars, then, is to investigate why

these major trade routes did not facilitate more apparent

cultural exchanges, rather than merely attempting to prove a

direct link. The absence of such a cultural interplay along

these significant routes would be quite remarkable.

The pattern observed in Christian scholarship, where there's a

tendency to deny or overlook Buddhist influence, appears to be

repeating in the study of Greek influence in India. This

suggests a recurring theme in historical research where the

extent of intercultural influences is often underestimated or

unacknowledged.

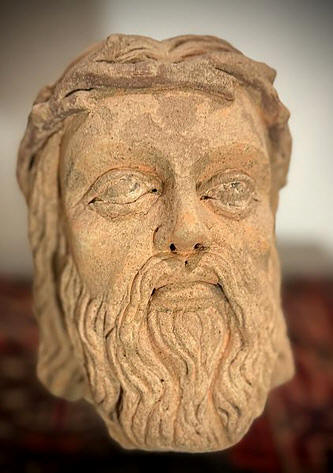

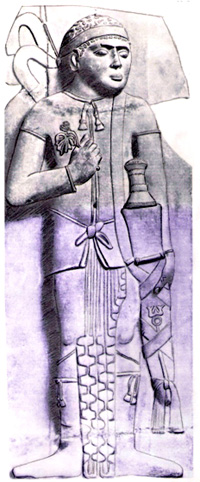

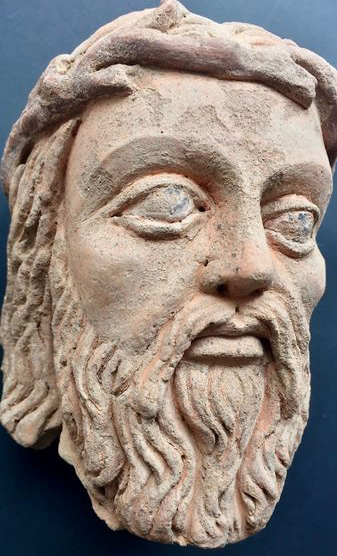

This terracotta sculpture represents a

remarkable confluence of Greek and Indian artistic traditions,

typical of the Greco-Buddhist art from the Gandhara region. The

hairstyle is elaborate, indicative of Indian artistic influence,

with curls and patterns that may reflect the sophisticated

sculptural Indian styles of the Mauryan period.

The half-closed eyes, denoting a

meditative state, are a common element in Buddhist

representations, conveying inner tranquility and spiritual

introspection. The forehead bears a third eye mark with three

rings, suggesting a connection to the Buddhist trinity, the

Borromean rings of

TRi-RaTNaS. Her elongated earlobes, another hallmark of

Buddha representations, denote wisdom and a departure from

worldly possessions.

Notably, the sculpture includes a nose ring, an adornment that

is not typically found in Greek art, suggesting a strong Indian

cultural element. This detail adds to the overall synthesis of

the figure, marrying local traditions with foreign influences.

The nose ring could signify marital status, fashion, or even

spiritual significance within Indian culture.

Additionally, the full lips, pronounced chin, and the sensual

yet contemplative expression are reminiscent of Greek sculptural

art, known for its realistic portrayal of human subjects. The

combination of Hellenistic realism with Indian symbolism results

in a sculpture that is both physically alluring and spiritually

resonant.

This piece stands as a testament to the cultural dialogue

facilitated by the Silk Road, where Greek realism met and melded

with the spiritual iconography of Indian art.

Johanna

Hanink's interpretation

of Greco-Buddhism as a reflection of European scholarly

reluctance to acknowledge native contributions to the "pleasing

proportions and elegant poses of sculptures from ancient

Gandhara," as noted by

Michael

Falser, challenges the

notion of "Buddhist art with a Greek 'essence'" as a colonial

construct emerging during British rule in India. This

perspective, as it intersects with the depiction of the Indian

woman, introduces a contentious angle in scholarly

interpretation, where the debate shifts from religious bias to

what could be perceived as left-wing political agendas. In this

light, it's not merely old European colonial perspectives

painting Indian art with Greek hues, but a modern inclination to

dismantle our colonial history under a lens of guilt. These

views, arguably 'woke,' represent another form of colonial

imposition, marked by an unrecognized Western ignorance of

Eastern history. This approach reframes cultural exchange as

cultural appropriation, seen solely through the prism of power

and dominance, further complicating our understanding of

historical intercultural interactions

The above depiction's specific features is evidence of a direct representation of

the cultural syncretism in the Seleucid Empire. This might

suggest to scholars like Hanink or Falser that cultural

intermingling was (and is) a complex, two-way process, with

influences flowing in both directions, rather than a simple case

of colonial imposition.

The overall environment of cultural synthesis provided by the

Silk Roads created an atmosphere where similar spiritual

expressions arose over thousands of kilometers. Thus, a more

inclusive historical view recognizes the Silk Roads not just as

trade routes but as channels for a dynamic cultural and

religious dialogue that has shaped the world in more ways than

is credited.

This perspective offers a valuable counterpoint to the

traditional nation-centric view of historical development. The

concept of "countries" as we understand them today is a

relatively recent development in human history, and their

borders have often been fluid and subject to change. In

contrast, trade routes such as the Silk Roads predate many

modern nations and have served as continuous channels for

interaction and exchange for millennia.

In accordance, the coming text will view trade routes as

cultural entities in their own right, fostering a level of

cultural homogeneity that might surpass that of the countries

they pass through. These routes acted as arteries of commerce,

yes, but also of ideas, religions, languages, art, and

technologies. As such, they could cultivate their own unique

cultures, which were defined not by national borders but by the

flow of goods and knowledge.

The Silk Roads as a Civilizational Zone

The Silk Roads connected a series of civilizations from the

Chinese Han Empire to the Mediterranean, creating a

supercultural zone where East and West could meet and mingle in

ways that transcended the political or cultural policies of any

single empire or nation-state along its length. The result was a

kind of Silk Road culture that, while not homogenous in the

strictest sense, shared a set of common values, practices, and

understandings shaped by the necessities of trade and the

exchange of ideas.

This perspective aligns with the concept of "cultural spheres"

or "civilizational zones," where the defining characteristics of

a region's culture are not determined by the political

boundaries of states, but by the historical, geographical, and

cultural ties that bind different peoples together. It suggests

a view of history as a tapestry woven from threads of human

interaction that are often far broader and more complex than

national narratives allow for.

The adage "follow the money" aptly applies to the Silk Road's

cultural dynamics. This ancient trade network fostered a shared

civilizational experience marked by fluidity and openness to

external influences, contrasting with the more rigid structures

of nation-states. In this context, the cultures along the Silk

Road prioritized connectivity and mutual influence, favoring a

collective development over isolation and independent growth.

This perspective underscores the significant role of trade and

economic interactions in shaping cultural and historical

landscapes.

ALEXANDER THE

GREAT IN INDIA

The key influence in the

ongoing construction of Buddhism was the introduction of Greek

philosophy. Homer was translated into Indian languages, and the

story of the Trojan Horse became part of the folklore on the

Ganges plains.

However, the influence also went the other way, as far back as

to Greece. Alexander the Great, in addition to his formidable

military skills, was philosophically inclined. His father,

Philip of Macedonia, brought Aristotle from Athens to tutor

Alexander. Alexander chose prominent philosophers

Pyrrho,

Anaxarchus,

and

Onesicritus

to accompany him on his conquest of India.

The Cultural Openness of Alexander

Generally, Greek culture was unimpressed and often disinterested

in foreign philosophies and religions. Gods of other lands were

traditionally understood not on their own terms but as locally

adapted Greek gods. Thus, the Indian god Krishna became

Hercules. From Aristotle's Macedonian-Greek perspective,

barbarians, those who did not speak Greek, were lower beings

whom the Greeks were meant to rule over. The idea of seeking

philosophical inspiration outside Greece seemed unlikely.

However, in this respect, it is of crucial importance to

mention the following: Alexander did not follow his tutor

Aristotle's opinions in this regard. The respect Alexander

showed for Persian and Egyptian culture was almost heretical in

this context, and this openness paved the way for Greek

philosophers' unusual respect and attentiveness towards India's

naked ascetics, whom the Greeks called gymnosophists. Where

Greek philosophers often provoked disgust in other cultures for

their tradition of philosophizing naked, they met in India's

ascetics a culture that practiced the same form of philosophical

nudity.

Onesicritus and the sun's naked sages

Onesicritus, a student of Diogenes, had remarkable

encounters with Indian sages, the gymnosophists. In Taxila, he

met a group of naked sages on a small hill in the scorching

midday sun. Their demand for him to undress as a condition for

discussion probably seemed familiar, as Greek philosophers also

had the habit of discussing naked. The fact that Indian sages

sat unimpressed in the burning sun and only wanted to discuss

here earned Onesicritus' respect but was not alien to a man

whose mentor was Diogenes in the barrel.

Diogenes, as the archetype of the provocative holy fool who

scornfully sat outside society's rules, would undoubtedly be

recognized by India's wise men.

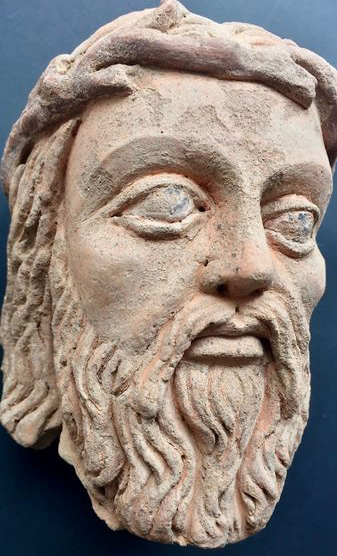

This Bactrian terracotta figurine embodies the

fusion of Hellenistic and indigenous artistic influences. The

figure's posture and stylized wings echo Greek representations

of deities and mythological figures, such as Eros or Nike. The

facial features, with a prominent beard and detailed hair,

resonate with the classical Greek style of portraying mature

male figures, emphasizing individuality and expression. The

craftsmanship and the figure's attire, including the drapery's

folds, reveal a Hellenistic touch, a common trait in the

region's iconography following Alexander the Great's incursion

into Central Asia and the subsequent cultural syncretism.

The terra cotta figure from Bactria shares several parallels

with depictions of Diogenes, the Greek philosopher: Cynic

Philosophy Representation: Diogenes is often depicted in a

simple cloak, embodying the Cynic philosophy of living in

accordance with nature and rejecting material possessions. The

figure's simple attire may reflect this philosophy. Ascetic

Lifestyle: Diogenes was known for his ascetic lifestyle, which

is also a common theme in Buddhist representations. The figure's

modest clothing and humble posture could symbolize a similar

asceticism. Beard and Hair: The detailed beard and hair are

reminiscent of classical Greek depictions of philosophers, among

whom Diogenes is one of the most iconic. Posture and Expression:

Diogenes was famous for his provocative actions and disdain for

societal norms. The seated posture and the facial expression of

the figure, which could be interpreted as contemplative or

challenging, might draw a parallel to Diogenes' own public

demeanor. Wings: While Diogenes himself was not associated with

wings, the Greek god Hermes was, and he was a messenger who

traversed between the divine and mortal worlds. Diogenes'

philosophy attempted to transcend conventional life, which could

be symbolically represented by wings. These elements combined

may suggest a fusion of Greek philosophical iconography with

local Bactrian cultural motifs, portraying a figure that echoes

the spirit of Diogenes in a new cultural context.

Visiting the sacred city of

Varanasi, one often meets Indian sadhus, modern embodiments of

the ancient philosopher Diogenes. The terracotta figure, similar

to numerous others, serves as a testament to these encounters.

These interactions, where the lifestyles of Indian ascetics

affirmed the principles of Diogenes, became ingrained in the

cultural memory of both Greek and later European societies,

honoring the wisdom of Indian gymnosophists. Subsequently,

figures such as the English Puritans recognized these sages as

precursors to their own ascetic practices.

Calanus - the army's sage

There are many indirect indicators of this compatibility between

Greek and Indian culture. That philosophers from the two

cultures could meet in dialogue is perhaps natural, but even the

ordinary soldier in Alexander's army could apparently

respectfully recognize the Indian ascetic's lifestyle and value

norms.

A naked sadhu from Taxila, named by the Greeks as

Calanus, had

just completed his obligatory 37 years as a hermit and was now

free to do what he wanted. He joined Alexander and became a

popular mascot for the army. Calanus became the army's guru,

giving satsang, i.e., teaching officers and soldiers in the army

his philosophy. The extent to which the army had taken the naked

sadhu to their heart became clear when Calanus later decided to

leave his body at the age of 79 in Susa, Persia, by burning

himself alive in a dramatic ceremony, with Alexander and his

entire army as spectators. As he was carried smiling into the

flames, he was hailed by war cries and the trumpeting of

elephants from Alexander's army. At this point, Calanus had

become the army's spiritual guide, and his death was later taken

by the army as a sign of Alexander's own too early death.

Considering the abundance of similar small terracotta figures

discovered in Afghanistan, it is plausible to speculate that the

depicted sadhu may represent Calanus.

Clearchus

The philosopher

Clearchus of Soli, probably a student of Aristotle, traveled

with wisdom from Delphi to Oxus in India and later described in

his pamphlets philosophical duels between Greek philosophers and

Indian sages, where he let Indian wisdom triumph over the Greek.

India's remembrance of Alexander

India has always understood itself through myths, through

stories.

Even today in India, there are many folk tales about Alexander,

especially his interest in India's philosophers, the wise

sadhus.

To what extent Alexander's presence has influenced India can

also be glimpsed through these still-living stories. I spent

almost a year in the Indian state of Punjab, where it struck me

how much the meeting with Alexander is still remembered by the

people. In Punjab, I heard a man put another in his place by

saying: In the end, you are no more worth than one of Porus's

elephants. King Porus's elephant army was immediately

defeated by Alexander upon his entry into India in 326.

THE SELEUCID EMPIRE

In the period following Alexander the Great's death, the

Seleucid Empire, which encompassed much of the former Persian

Empire, played a pivotal role in the cultural exchange between

Hellenism and Buddhism. It was founded by

Seleucus Nicator I (358 – 281 BC), a distinguished general

of Alexander.

The Seleucid Openness

In noting the unique approach of Seleucus I Nicator, one of

Alexander's successors, it's crucial to recognize his

continuation of Alexander's 'un-Greek' respect and openness

towards 'barbarians', conditional on their submission to his

rule.

Seleucus I Nicator was among the few generals of Alexander who

supported Alexander's deliberate policy of cultural

amalgamation. This policy notably included the mass forced

marriage of his officer corps to women from ocupied countries,

especially from Persia, but later also from India. Remarkably,

Seleucus' own marriage with the

Sogdian noble

woman, Apama,

was one of the few such cross-cultural unions that survived

Alexander's death.

This successful marriage set the

tone for a Seleucid realm that was politically and militarily

aggressive, but exceptionally tolerant in terms of cultural

diversity. The son born from this mixed marriage, Antiochus I,

was fully recognized by his father and played a significant role

as a conciliator between the Persian elite and the emerging

Hellenistic ruling class.

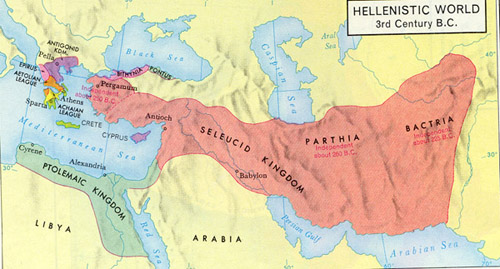

The Unique Geopolitical

Conditions of the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire, in terms of sheer longitudinal span,

was one of the most elongated empires of the ancient world. It

stretched over 3,000 kilometers from the Aegean Sea in the west

to the Indus Valley in the east, creating a vast territory that

connected the Greek world with the rich cultures of the Near and

Middle East and Central Asia.

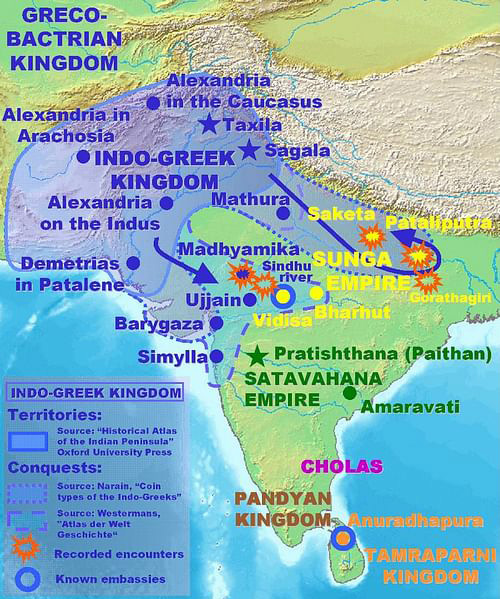

The Seleucid Empire was known for its extraordinary religious

tolerance and cultural openness. Stretching from India to

Turkey, this empire provided a unique melting pot where diverse

religious and cultural ideas could intermingle, potentially

including the philosophical and spiritual tenets of Buddhism and

early Christianity. As depicted in the accompanying map, it is

quite apt to view the Seleucid Empire not just as a political

entity but as a massive trading route in itself. The Empire

acted as a bridge between the East and West, facilitating the

flow of goods, cultures, ideas, and technologies across its vast

expanse. It connected the Hellenistic world with the societies

of Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent.

The Challenge of Ruling a Wast Territory

Unlike

Ptolemy, another of Alexander's generals who took control of

Egypt—a small but fertile part of Alexander's legacy—Seleucus

faced entirely different challenges. He ruled over a vast

territory that united diverse cultures including Sumer, Elam,

Persia, Assyria, Phoenicia, Babylon, and later Asia Minor and

Palestine. This required an exceptional ability and willingness

to collaborate culturally.

No Seleucid Racial and Ethnic Exclusivity

This reflects why Cleopatra, who was of entirely Macedonian

origin, contrasts with the rulers of the Seleucid Empire, who

were an amalgamation of various cultures and ethnicities. This

diversity among the Seleucid rulers highlights their openness to

different backgrounds, differing from the more ethnically

homogeneous leadership in other post-Alexandrian geographically

much smaller empires.

Contrary to other post-Alexandrian empires, such as Ptolemaic

Egypt, the Seleucid Empire did not have a racial exclusivity

built into the highest echelons of its power structure. In this

way, it continued Alexander's ingenious policy—a blend of

localized feudalism and meritocratic governance. This approach

allowed anyone, regardless of their non-Macedonian origin, to

join the ranks of the powerful, provided they had earned it

through merit or were of noble birth. However, a prerequisite

for membership in this new elite circle was a mastery of the

Greek language and culture.

Polis Cultures on a String from

India to Greece

Recognizing that he couldn't consolidate his power solely by

relying on pre-existing cities, Seleucus Nicator opted to build

numerous new cities from scratch. These cities were vibrant

centers of Hellenistic polis culture, infused with

Macedonian-Greek traditions and civilization. Positioned like

pearls on a string, they also served as caravanserais and linked

India to the Middle East in a cultural exchange that lasted long

after the collapse of the Seleucid Empire and its Bactrian and

Indo-Greek successors.

Cultural Diffusion and Legacy in the Seleucid Empire

In the various Alexandrias and newly-founded Seleucias that

dotted the landscape of the Seleucid Empire, Hellenistic culture

became a marker of social capital. Speaking Greek and venerating

Greek gods were not just exercises in spirituality or

communication; they became synonymous with power and prosperity.

Local indigenous groups and their leaders, even those situated

far from the traditional Greek heartland, adopted the Greek

language and partook in Greek theatrical productions as a form

of cultural assimilation that had direct social and economic

benefits.

A Second Wave of Hellenistic Migration

The formation of the Seleucid Empire facilitated a second

wave of migration, distinct from the initial military

expeditions. This time, the people who set out for new lands

were not just soldiers but commoners—artisans, scribes,

philosophers, and scientists from Macedonia and Greece. Their

journey for a better life in the newly-established cities of the

Seleucid Empire echoes the 19th-century mass migration to

America. These new settlers left an indelible, albeit often

overlooked, imprint on the cultural and intellectual landscape

of the East.

The Seleucid experiment in cultural fusion had long-lasting

implications, not just in terms of the flow of goods along the

burgeoning trade routes, but also in the spread of ideas and

traditions. It became a vibrant hub of cultural exchange, laying

the foundation for future civilizations to build upon.

The Seleucid Empire seen as a Civilizational Zone

Examining historical examples, the

Seleucid

Empire emerges as a key illustration of the civilizational

zones concept. This empire, a confluence of diverse languages

and cultures, demonstrates the intricate dynamics of cultural

and historical evolution in vast empires. Analysis of the

Seleucid Empire through the lens of civilizational zones

highlights how varied cultural and linguistic groups were

unified and interacted under its expansive rule, weaving an

intricate tapestry of interconnected histories.

Intriguingly, within this context, a form of abstract universal

goodness, akin to Buddhist principles, emerged as the lingua

franca, facilitating cohesion and communication across this vast

empire, and exemplifying the significant role of shared

philosophical and ethical frameworks in the unification of large

and diverse territories.

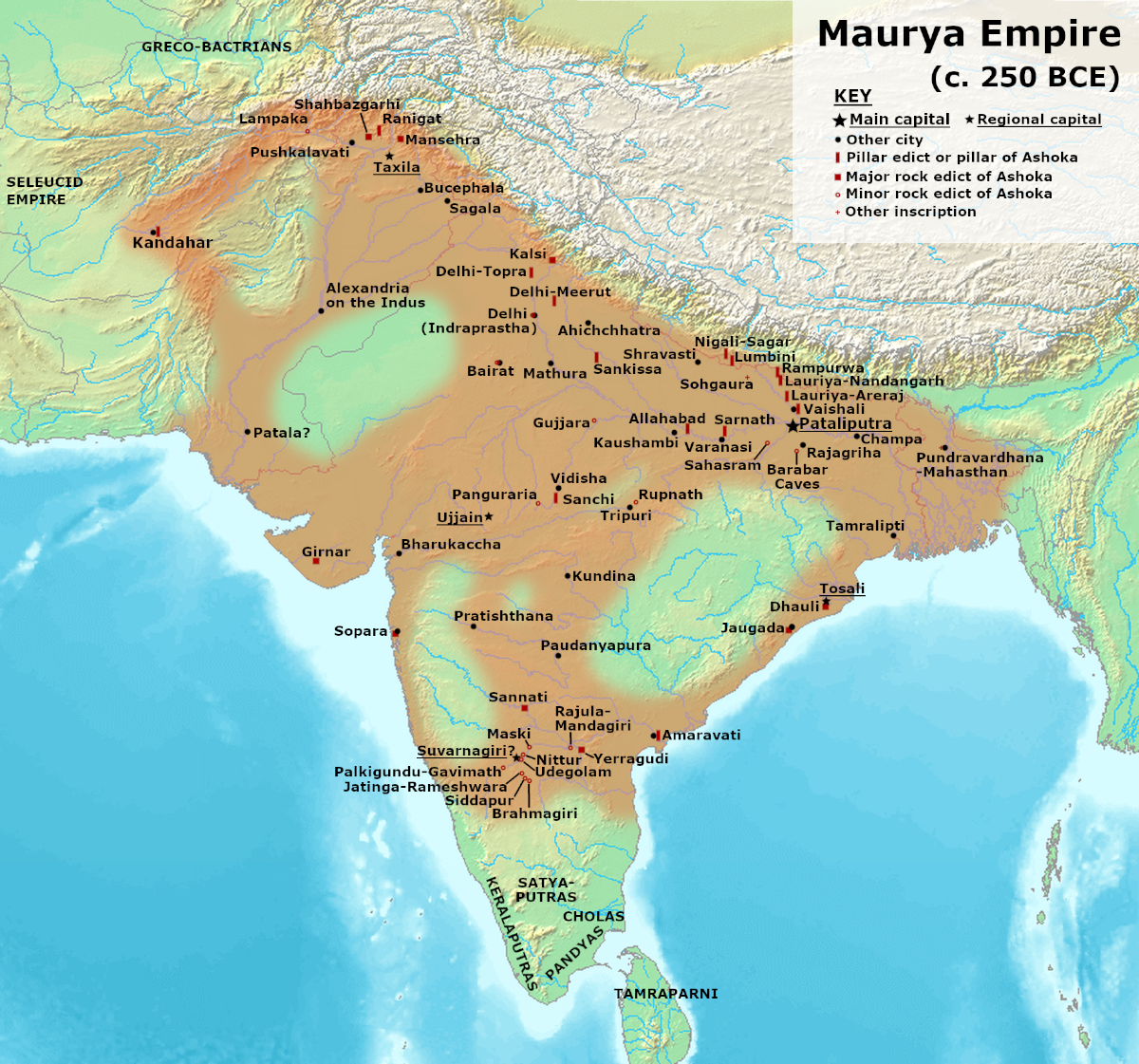

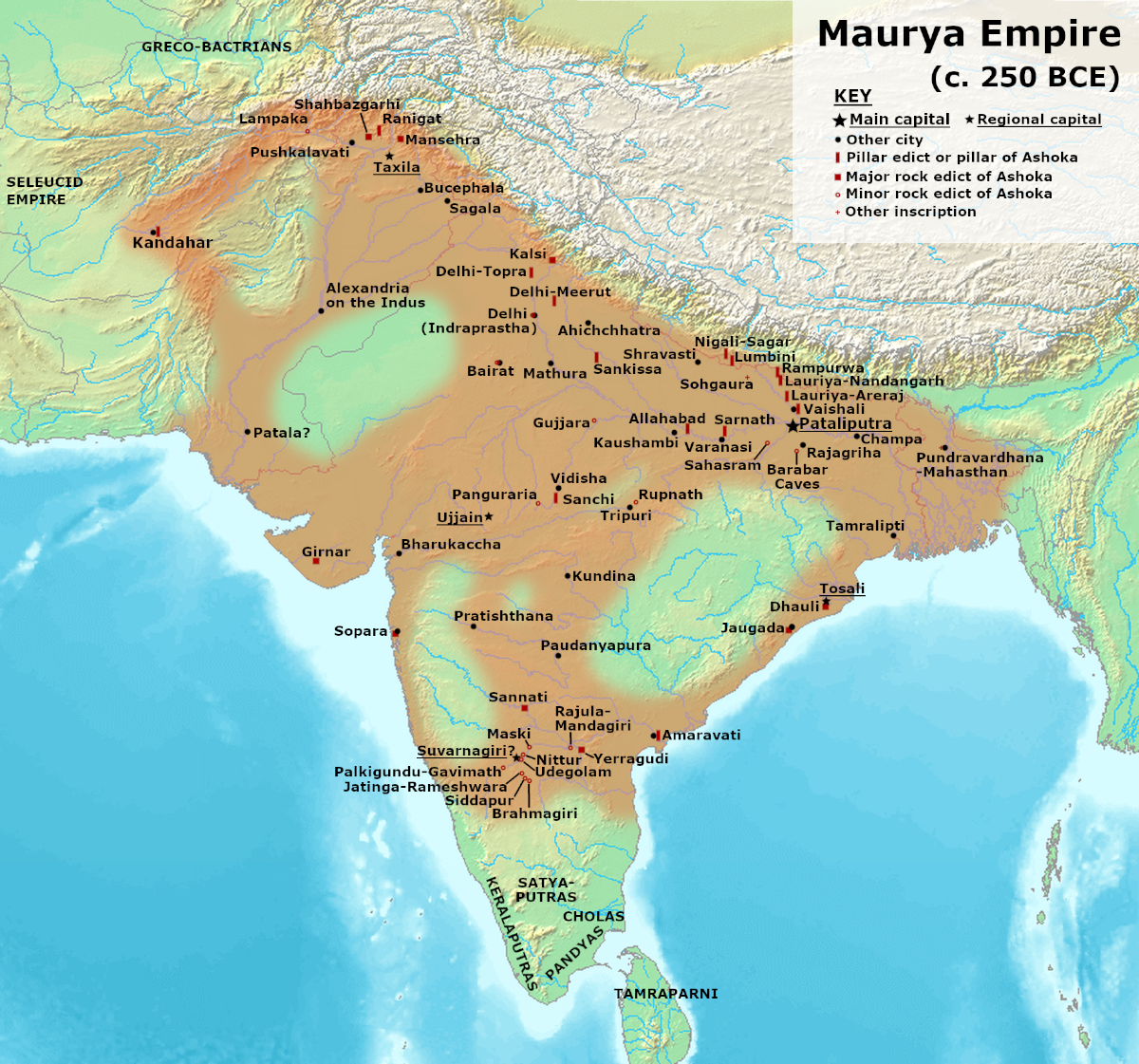

THE MAURYAN EMPIRE

In India itself, the rise of power centers during the

contemporary Mauryan dynasty led to the creation of wealthy

Gangetic mega-cities. This urbanization necessitated, like the

case was in the Seleucid Empire, a state capable of overseeing

long-distance trade and production. Elements of the warrior

caste evolved into a new state caste, focused on the

ever-growing need to regulate trade and infrastructure.

Chandragupta Maurya: India's

Great Low-Caste King

Chandragupta Maurya (340-298 BCE), the grandfather of

Ashoka, was a

man of humble origins, born into the

shudra,

the lowest caste in the societal hierarchy. Alongside

Chanakya, a

Brahmin who

felt betrayed by his own caste, Chandragupta orchestrated a

social revolution that dethroned the preceding

Nanda

dynasty. This marked the inception of the formidable

Mauryan

empire.

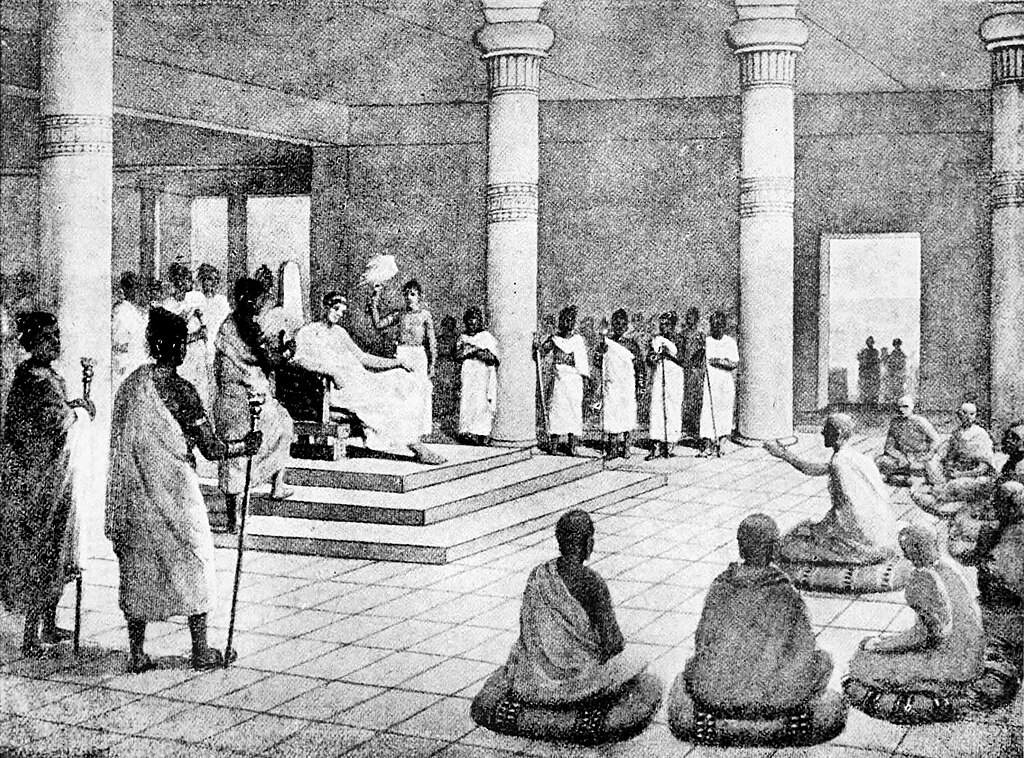

The Seleucid ambassador

Megasthenes

meticulously documented the Mauryan dynasty around 300 BCE while

residing at Chandragupta's court in the capital, Pataliputra—now

modern-day Patna, in the Indian state of Bihar.

Chandragupta's rise to power coincided with Alexander the

Great's arrival in Northwestern India in 326 BCE. Ancient

historians recount that Dhana Nanda, the ruler of the Nanda

dynasty, was despised in his own country for his low birth.

Alexander received emissaries from the disgruntled Brahmin caste

who offered assistance in overthrowing Dhana Nanda. However,

Alexander had to abandon his conquest plans when his own army

rebelled against marching further into India.

Both the Nanda and Maurya dynasties were led by individuals from

the lower rungs of the Indian caste system. It is plausible to

consider these low-caste dynasties as products of the social

chaos induced by the affluent cities along the Ganges and

Alexander's military disruption of the North-western region of

India.

Chandragupta's encounter with Alexander's campaign was pivotal.

The prevalence of both the Nanda and Mauryan dynasties

underscored how the emergence of Buddhism coincided with a

period of social upheaval that especially disrupted the

established caste system.

The Persian Legacy

For thousands of years, Persian culture has exerted a

significant impact on Northern India. The formidable Persian

Empire repeatedly extended its reach into the northwestern

regions of the Indian subcontinent. A testament to this

influence is the very name 'India' itself, which derives from

the Persian inability to pronounce the letter 's,' transforming

'Sindh,' a province in what is now Pakistan, into 'Hindh.' This

linguistic adaptation gave rise to the terms 'Hindustan' and

'Hindus,' underscoring the depth of Persian cultural imprint on

India.

Northern India, particularly in the period just before the rise

of the Mauryan dynasty, received significant civilizational

inputs from the most powerful empire of the time, the

Achaemenid Persia. The Persians utilized the social

fragmentation of the caste system to efficiently divide and

conquer. It is reasonable to speculate that the low-caste kings

like Chandragupta received aid from Achaemenid Persia, which

sought buffer states along its eastern borders.

Chandragupta's realm was situated in what is today the state of

Bihar, a region that has retained a stronger Persian influence

than any other Indian states, an influence that is still evident

today.

Chandragupta and Chanakya's military strength could only have

originated from Persian military forces, particularly the

fragmented units that roamed into India during the chaos

following both Alexander's conquests and later his death.

Once Chandragupta had consolidated power, he modeled his

governance after Persian prototypes, even positioning himself as

an Indian replica of a Persian king. Numerous examples

illustrate the Mauryan dynasty's flirtation with Persian

culture. Chandragupta even had a cadre of female Amazonian

warriors, much like his Persian contemporaries. Early

administrative scripts in India also owe a debt to Achaemenid

Persia. Chandragupta's palaces were also constructed in

accordance with Persian prototypes. Reflecting on the ruins of

the Mauryan palaces in Patna, Rowland notes:

"The first indication of the

tremendous influence exerted on Mauryan India by the art of the

Achaemenid Empire ... the conscious adoption of the Iranian

palace plan by the Mauryas was only part of the paraphernalia of

imperialism imported from the West."

We might surmise that

Chandragupta, being an outsider to the Indian caste system, felt

little obligation to continue the cultural traditions of his

predecessors, making it easier for him to build his ideology and

power structure from an eclectic perspective.

Thus, Chandragupta Maurya was not just a great king who ascended

from the lowest echelons of society; he was a transformative

figure whose rule was significantly influenced by external

cultures, particularly Persia, which allowed him to challenge

and overturn the traditional caste hierarchies in India. This

overturn pawed the way for long-distance trade and urban life to

flourish.

THE MAURYAN-SELEUCID PEACE AGREEMENT

An important condition for the caravaic expansion was the

good relations between the Seleucid and the Mauryan empire.

Following Alexander the Great's conquests, the Seleucid Empire,

among the most influential successors, adopted a strategy of

guardedness towards the west but showed an inviting openness

towards the east. It's in this eastern realm that they

encountered the Mauryan Empire.

The unique survival strategy of the Seleucid Empire hinged on

Seleucus I Nicator's remarkable ability—honed in the days of

Alexander the Great—to build cultural bridges which again

translated into trading bridges. The turning point for the

empire's destiny was its encounter with India. Originally

beginning as a military confrontation in 305 BCE, it evolved

into a harmonious cultural exchange with the powerful Maurya

Dynasty. As a symbol of peace and friendship, Seleucus arranged

the marriage of his daughter to Chandragupta Maurya, forming an

alliance that would last for generations. In this exchange,

Seleucus ceded territories up to the Hindu Kush mountains, while

receiving 500 war elephants in return. These elephants later

proved to be a decisive force in the pivotal

Battle

of Ipsus

in Turkey in 301 BCE. The Seleucid strategy henceforth involved

peace towards the east and war to the west.

Chandragupta, aligned with the social openness of Seleucus

Nicator, granted Greeks in Kandahar the right to marry into any

Indian caste, highlighting a softened stance towards the

Brahminical caste system during the Mauryan period.

The peace treaty had a profound

impact on the later rise of the Ashokan-Mauryan Dynasty as the

world's first and largest "peace empire." Shielded by his

Macedonian friends to the northwest, Ashoka could safely convert

his empire to the non-violence of Buddhism, even implementing

laws for animal welfare. Without the predeceding Seleucid-Maurya

alliance, Ashoka's benevolent rule and the expansion of Buddhism

would have been impossible.

The Mauryan Openness versus the Exclusiveness of the Brahmans

The Brahmans, traditional custodians of Indian knowledge,

exhibited a reluctance to engage with foreign cultures, as

captured by Sir William Jones' observation that the Brahmans

seldom borrowed from Greeks or Arabs:

The Brahmans are always too proud to borrow

their

science from the Greeks, Arabs or any nation of the

Mlechchas as they call those who are ignorant of the Vedas.

Yet, the cultural panorama had

changed in India under the Mauryan Empire. Brahmins were loosing

power. Chandragupta Maurya, having interacted with Alexander's

Greeks, appreciated Hellenistic influences. His disruptive

Persian ouview together with his lower cast background pawed the

way for curiosity and social experimantation. Chandragupta's

religious outview was furthermore rooted in Janism, an Indian

minority religion that lived outside the laws' of

Manu's cast

system.

At the previous mentioned peace agreement in 305 B.C.,

Chandragupta's acquisition of territory up to Hindu Kush, also

incuded the annexation of the Greek city of Alexandria Arachosia

(modern-day Kandahar or Gandhara in Persian) Chandragupta

allowed it to flourish under Hellenistic ideals.

Cultural Synthesis

The Seleucid-Indian friendship led to the flow of Indian

wisdom into the Seleucid Empire, while Hellenistic wisdom

enriched Northwestern India. In this cross-cultural melting pot,

new Greco-Indian syncretic religions began to emerge, most

notably Buddhist culture blending harmoniously with Hellenism.

Kandahar became an important center of cultural fusion. This

city and the smaller cities around it, rich in Hellenistic art

and architecture, became significant nexuses between Indian and

Hellenistic culture.

Lasting Impact from the first Seleucid-Indian Alliance

The Mauryan ethos, free from the constraints of caste,

readily imbibed Hellenistic influences, as seen in evolving

Indian statuary and art. Centuries after Alexander, Greek

statues of Zeus, Odysses and Pericles were seen alongside

various depictions of Buddha and Indian Gods.

The cross-cultural friendship ensured that the Mauryan Dynasty

would maintain a cordial diplomatic relationship with the

Seleucid Empire. Seleucus sent an ambassador named

Megasthenes

to Chandragupta's court in Pataliputra. Successive Mauryan

rulers like

Bindusara

and Ashoka continued these diplomatic relations through exchange

of ambassadors.

Though the sprawling Seleucid Empire was eventually replaced by

a series of smaller Greek states, the original Greek-Indian

alliance significantly shaped the region from India to the

Middle East for centuries.

ASHOKA THE GREAT

It is indeed remarkable how the influence of one of the

world's largest empires has been overlooked in Western

historiography. Only the author H.G. Wells seems to afford

Ashoka the

recognition he deserves, stating:

"His (Ashoka's)

reign for eight-and-twenty years was one of

the brightest interludes in the troubled history of mankind."

In the era preceding the end of

the Punic Wars, which heralded the rise of the mighty Roman

Empire, and after Macedonia had lost its leading role with the

death of Alexander the Great, a new and powerful India emerged.

This resurgence was fueled by flourishing trade, skilled

craftsmanship, and agriculture.

Ashoka,

the grandson of Chandragupta Maurya, is revered as one of the

greatest and most enlightened rulers in Indian history. His

reign marks the zenith of the Mauryan dynasty. Initially known

as "Ashoka the Terrible" in his impetuous youth, he was a

ruthless warlord who expanded his territory while orchestrating

a brutal campaign against Brahmins and Buddhists alike. The

bounty for a severed head of a Brahmin was a staggering 100

dinars.

However, Ashoka underwent a profound transformation after

converting to Buddhism. His rule brought peace, order, and

systematic governance to a vast Indian empire that stretched

from southern India to Burma in the east and as far west as the

eastern parts of Persia.

Following a period of extreme violence, including the

devastating

Kalinga war, Ashoka's empire metamorphosed into the world's

first humanitarian superstate. He crafted a realm that thrived

through wisdom and moral authority rather than the force of the

sword.

Ashoka's governance followed a pattern that would later become a

historical archetype for warlords who, after

consolidating their power, ushered in long periods of peace

and prosperity.Inheriting the Mauryan dynasty's liberal

policies, inspired by Persian governance, Ashoka allowed social

mobility based on merit, rather than caste or religious

affiliation. While the caste system remained in place, it lost

the rigidity that characterized it before and after this period

in Indian history. Ashoka's transformative reign remains a

pivotal chapter in Indian history, highlighting the enduring

impact of ethical leadership and the unifying power of shared

humanitarian values.

Long-distance Infrastructure

A key factor in the rise and consolidation of this expansive

empire was the construction of an elaborate network of roads.

These roads acted as the lifeblood of the empire, connecting

India's multi-ethnic and multicultural tapestry into a cohesive

unit.

In this period the trade routes expanded to such an extent that

it became impossible to guard them against attacks through state

governed policing power. Ashoka 'realized' that control over the

mind is much more efficient than control over the body when it

comes down to the securing of peace in inter-dependent trading

mega-cities. Hence Buddhism became suitable as a state religion.

The Rise of

Ashoka-Buddhism

Before Ashoka, Buddha was regarded as not much more than a

local hero among hundred other saints on the Gangetic plains.

However, under Ashoka's reign, Buddhism entered an unprecedented

period of expansion. Despite its limited spread and influence in

the first few centuries after Buddha, it wasn't until Ashoka's

conversion to Buddhism around 250 BCE that this religion gained

significant momentum. This momentum eventually propelled

Buddhism into becoming one of the world's major religions.

During this period Buddhism transformed into a pragmatic state

religion. The individual quest for Nirvana took a backseat to a

state-sponsored moral doctrine. This doctrine was particularly

tailored for the prosperous city-dwellers, merchants and

artisans, keeping in mind the diverse feudal mini-states that

made up most of India at the time.

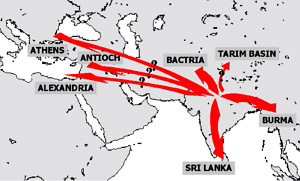

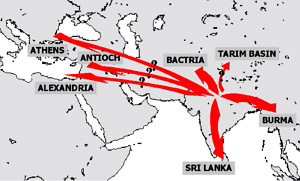

With Ashoka's conversion, a global dissemination of the

revolutionary and still-relevant teachings of the Buddha began.

Ashoka initiated a large-scale missionary effort based on

Buddha's own call for spreading the faith, a mission anchored in

the power of example:

"Oh Monks! Travel far and wide

to benefit many, out of compassion for the world, for the

advantage of gods and mortals alike. And let not two of you take

the same route. Preach the doctrine that leads to goodness.

Preach it in spirit and in letter. Show through your own

immaculate lives how religious life ought to be lived."

(Buddha)

Buddhism's missionary routes

In Ashoka's version of missionary

Buddhism, the focus lay on practical tenets for everyday living

rather than intricate philosophical discourse or deification of

the Buddha. The teachings emphasized the essence of the

philosophy over the personage of the Buddha himself.

The Universities of Taxila and Nalanda

During Ashoka's peaceful reign, the early formations of

university culture began to surface. Taxila, a city that

flourished in this period, became a global center for

intellectual thought. Frequently referenced in

Buddhist Jataka tales, Taxila exemplifies how intellectual

and spiritual ideas managed to permeate all levels of society.

The city symbolized the inclusiveness of Buddhism under Ashoka,

uniting elite and commoner through shared spiritual practices.

Similarly, Nalanda University in the vicinity of Patna would

later take up the torch, profoundly shaping Buddhism even up to

the Gupta era.

The Ashokan Pillars

Inspired by Persian aesthetics, Ashoka erected towering 15-meter

sandstone pillars across his kingdom. Some were adorned with

four lion heads symbolically

proclaiming the Buddha's teachings of Dharma in all directions.

These pillars were engraved with easily digestible moral

principles, as encapsulated in Ashoka Pillar Edict Nb2 (S.

Dharmika):

"Dharma is good,

but what

constitutes Dharma?

It includes little evil, much good, kindness,

generosity, truthfulness and purity."

Ashoka Pilar Edict Nb2 (S.

Dharmika)

In an unprecedented move, Ashoka

also had his edicts inscribed in impeccable Greek, targeting

regions under Hellenistic control.

No Personality Cult

Ashoka's edicts made no mention of Buddha, and there wasn't a

single statue of Buddha from that time. The edicts emphasized

practical life rules rather than theology. With the combined

force of Ashoka's visionary Buddhism and the state's power, what

might be termed the world's first secular state was born.

The state adopted a rational form of Buddhism, viewing it as an

"enlightened" means of socio-spiritual regulation for life along

trade routes and within cities. The growth of trade routes

depended on wast geographic higway shaped areas of peace and

trust, for without them, long distance trading caravans, often

traversing hundred of kilometers without sufficient policing

infrastucture risked robbery and collapse.

Emperor Ashoka, a paramount figure in the proliferation of

Buddhism, is credited with the establishment of 84,000 stupas

and a multitude of monasteries across his empire, strategically

placed within bustling trade hubs to maximize their influence

and accessibility. This monumental effort was not confined to

his domain alone; evidence of such Buddhist structures extends

as far as Persia and even Syria. Theravada texts from Sri Lanka

notably mention a significant presence of Buddhist monastic

communities in Syria, indicating the widespread reach of

Buddhism during this period. This cross-cultural expansion

reflects the far-reaching impact of Ashoka's missionary

endeavors, disseminating Buddhist teachings well beyond the

Indian subcontinent.

The Spread of Ashoka-Buddhism

Edicts on pillars, stupas, academic institutions, and

state-endorsed monasteries and missionaries, all played a part

in the spread of Ashoka's practical moral teachings. This ethos

of self-regulation was gently impressed upon both the caravan

travelers and urban dwellers alike. Under Ashoka's guidance,

Buddhism flourished, contributing to what could be considered

the emergence of the world's inaugural secular governance. It

became the civilizational adhesive that united a diverse

populace, facilitating trade and communal harmony across vast

expanses.

In this sense,

Ashokan monasteries were not just religious retreats; they were

training grounds for self-discipline, while the wandering monks

were the deliverers of moral guidance. Ashoka's interpretation

of Buddhism provided a progressive blueprint for complex

long-distance societal organization, promoting sustained trade

and urban collaboration. In the era of Ashoka, monasteries

became centers for cultivating discipline, and Buddhist monks

emerged as devilery men of the 'dharmic interface'.

Ashoka's 'Buddhification' of Hellenistic Rulers

Under Ashoka's reign, the intermingling of Greek and Indian

philosophies reached unparalleled heights. Notably, some of

Ashoka's first converts to Buddhism were

his Macedonian-Greek neighbors in the Northwestern regions.

Although Western history often understates this, Hellenistic

rulers possibly leaned towards, or even embraced, Buddhist

tenets. The 13th Edict by S. Dhammika lists several Greek kings,

with precise historical and geographical references, as

proponents or followers of Buddhism:

Antiochus II Theos, 261–246 BC - Seleucid Empire

Ptolemy II Philadelphus, 285–247 BC - Egypt

Antigonus Gonatas, 276–239 BC - Macedonia

Magas, 288–258 BC - Cyrenaica, current-day Libya

Alexander II, 272–255 BC - Epirus, Northwestern Greece

While it's possible that Ashoka may have embellished the extent

of these monarchs' conversions, the actual process of adopting

Buddhism during that period did not require elaborate rituals.

Therefore, it is likely that the said kings merely endorsed or

showed favor towards Buddhist tenets. This, however, underscores

the notable interactions and cultural exchanges between the

far-flung eastern and western boundaries of the vast Seleucid

Empire. A critical takeaway is that, even if Ashoka's claims

about the spread of Buddhistic conversion to distant regions

like Macedonia and Greece were overstated, Buddhist ways of

thinking were nonetheless recognized in these lands.

Considering the non-aggressive and broadly relatable essence of

its teachings, it is plausible to deduce that Buddhism cast a

significant sway far beyond its core region. To employ a

contemporary metaphor, Buddhism functioned akin to open-source

spiritual-behavioral software, notable for its remarkable

capacity to be tailored,customized, by its adherents.

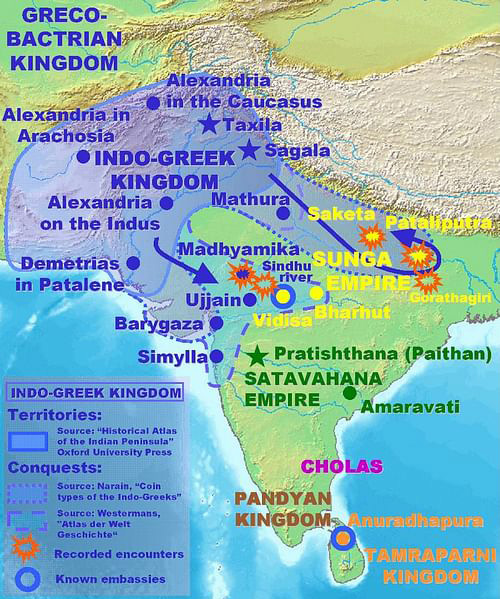

THE GRECO-BACTRIAN KINGDOM AND THE BUDDHIST KING MEANDER

The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, dating from around 256 to 125

BCE, was located in what is now Afghanistan, as well as parts of

modern-day Pakistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. The climate of

this region during the time of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom was,

backed by indirect evidence, likely more hospitable and fertile

than it is today, which would have supported the kingdom’s

immense prosperity.

Around the time of the fall of the Maurya Dynasty in 190 BC, the

Seleucid Empire began to slowly disintegrate, primarily due to

conflicts with the emerging Parthian Empire. Interestingly, the

Parthians adopted the Greek culture they observed in the

Seleucids. Even after the fragmentation of the Seleucid Empire,

the eastern satrap-kings maintained a good relationship with the

Mauryan Dynasty. The Bactrian satrap, before its independence in

255 BC and which represented the easternmost part of the

Seleucid Empire, had particularly strong ties with neighboring

India.

In 245 BCE, Diodotus I, a

Greek-Macedonian king, broke away from the Seleucid Empire to

establish his own state, Bactria. Concentrated with Greeks and

Macedonians, this region became a destination for political

exiles, much like Australia for England and Siberia for Russia.

Bactria continued and deepened the friendly relationship with

India, while focusing on defending against the constant

invasions from nomadic tribes to the north and northwest.

Subsequently, the King of the newly founded Bactrian kingdom,

Menander

(Melinda)

(r. 160-135 BC), emerged as one of the most

renowned converts to Buddhism.

Ruling around 150 BC, he governed

a territory spanning from Bactria (modern-day Afghanistan) to

parts of what is now northwestern India.

It is critical to highlight that the Buddhism Menander embraced

was significantly influenced by Hellenistic culture, having

undergone nearly a century of cultural interchange.

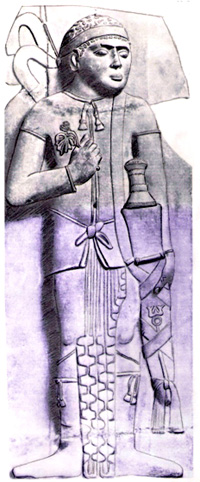

This relief from Orissa represents a Bactrian king, likely

Menander. The trinity symbol on his sword represents the Triple

Gem (Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha) in Buddhism.

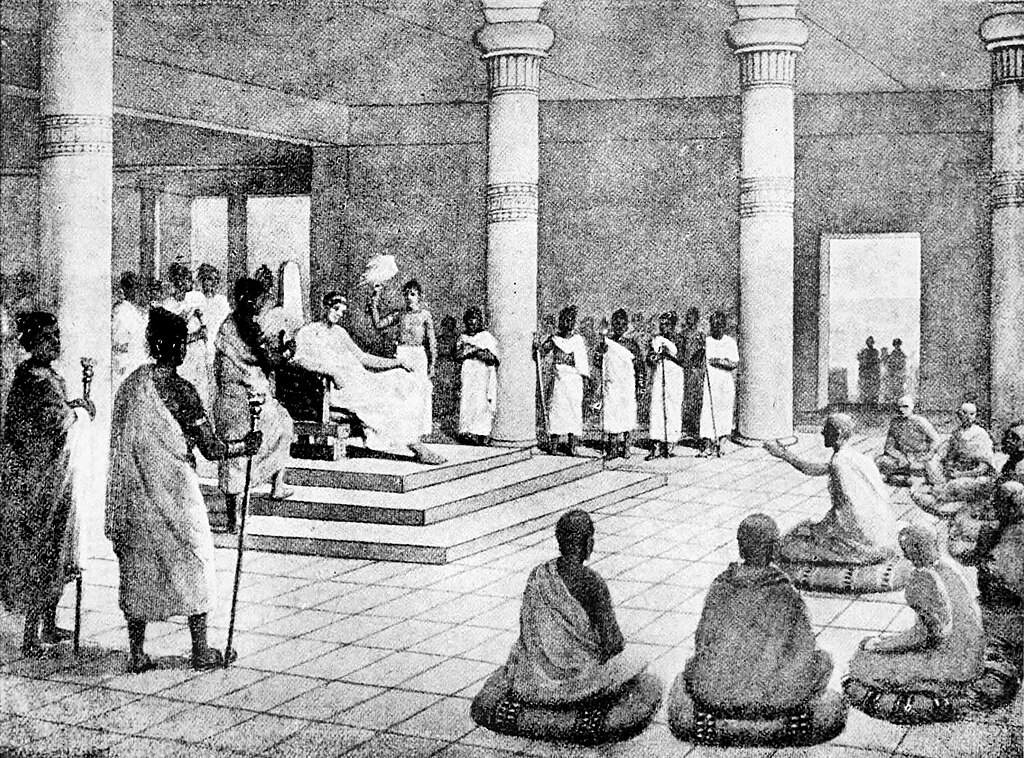

King

Meander/Melinda pose questions to his Buddhist teacher, Nagasena

During Menander's Greco-Buddhist

era, the Indo-Greek cultural synthesis reached an unprecedented

zenith. Notably, many valuable Indo-Greek artifacts in silver

and gold have been excavated. This, combined with the exquisite

coinage—which artistically surpasses even that of

Greece—indicates societies of great prosperity.

Portrait of King Meander/Melinda from a coin

Meander's predecessor, Demetrius I, had around 184 BC embarked

on a bold conquest deep into India. Here he founded the Indo

Greek Kingdom, where the Greeks even reached the new

Sunga

stronghold in

Pataliputra.

After this Eastern expansion

Taxila became