|

TRAUMA AND

SPIRITUALITY

"Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be

comforted."

(Matthew 5:4)

How should I begin this chapter? Perhaps with a statement that may

seem provocative:

True meditation can only truly unfold in a soul that has been wounded. It is a

gift uniquely reserved for those who have suffered deeply.

Certainly, everyone can benefit from a bit of mindfulness practice. However, the

true, transformative power of meditation lies in the hands of a soul in shock.

The Presence of God in Suffering

This is not a new idea. Throughout time, mystics from both the East and the

West have exemplified and highlighted this truth.

Ramana Maharshi, for instance, began his spiritual journey as a young 12 years

old boy after

the sudden death of his father. In India, with its long history of societal

upheavals in the form of powerty, famine and war, it was almost as though saints were forged through

loss and suffering.

In medieval Europe, Meister Eckhart often spoke of discovering God within

suffering. He taught that trials and hardships could bring one closer to the

divine if viewed as a part of God’s plan.

No one has captured the beauty and profundity of human suffering more eloquently

than the Sufis. Rumi once said, "There is a secret medicine given only to

those who are hurt so deeply they feel there is no hope."

Recently, I spoke with a young, successful man who recounted his own story. At

the age of five, he lost his grandfather, the person to whom he felt closest.

The loss overwhelmed him with anxiety, and he resisted going to kindergarten and

later to school. When he turned twelve, his parents invited him to attend a

Silva meditation course, where he might even learn to bend spoons, like Uri

Geller. Whether or not he ever bent a spoon, he found something far more

valuable: a glimpse of hope that empowered him to return to school.

Across cultures and centuries, whether from individual lives or the shared

stories of entire nations, we see the same message echoed: "What hurts you,

blesses you. Darkness is your candle." (Rumi)

THE REIGN OF THE AMYGDALA

Now the time has come to ask: Why is

suffering—and particularly trauma—so vital for spiritual unfolding? One apparent

answer lies in the impact of trauma, especially during childhood. Those who

endure such experiences often develop a deep-seated mistrust or distaste for the

external world, prompting an inward journey of self-exploration.

Interestingly, this same dynamic explains why spiritual circles often attract

conspiracy theorists. A childhood shock, especially one within the close family

setting, can lead to projections of mistrust—not only onto other people but also

onto larger systems, such as governmental or capitalist institutions. While we

won't delve into that rabbit hole here, it is a compelling parallel to consider

as we explore trauma as a gateway into the soul.

In recent years, I’ve noticed a recurring structural theme in the larger

Rorschach picture of spirituality and trauma. This theme points directly to the

amygdala.

While many New Age influencers have fixated on the pineal gland as the epicenter

of spirituality, my own explorations have led me down a different path—one that

highlights the central role of the amygdala.

This small, almond-shaped structure within the brain, often associated with fear

and emotional responses, may hold profound significance in the spiritual

unfolding of individuals shaped by trauma. It seems to serve not merely as a

center for processing emotional pain but also as a potential catalyst for deep

introspection and transformation.

It is now time to provide an example. The following excerpt is drawn from Arthur

Osborne's book,

The Teachings of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi - In His Own Words. In

this passage, Ramana recounts a life-altering experience he had at the age of

16.

"It was about six weeks before

I left Madura for good that the great change in my life took place. It was quite

sudden. I was sitting alone in a room on the first floor of my uncle’s house. I

seldom had any sickness, and on that day there was

"nothing wrong with my health, but a sudden violent fear of death overtook me.

There was nothing in my state of health to account for it, and I did not try to

account for it or to find out whether there was any reason for the fear. I just

felt “I am going to die” and began thinking what to do about it. It did not

occur to me to consult a doctor, or my elders or friends; I felt that I had to

solve the problem myself, there and then.

The shock of the fear of death drove my mind inwards and I said to myself

mentally, without actually framing the words: “Now death has come; what does it

mean? What is it that is dying? The body dies.” And I at once dramatized the

occurrence of death. I lay with my limbs stretched out stiff as though rigor

mortis had set in and imitated a corpse so as to give greater reality to the

enquiry. I held my breath and kept my lips tightly closed so that no sound could

escape, so that neither the word “I” nor any other word could be uttered. “Well

then,” I said to myself, “this body is dead. It will be carried stiff to the

burning ground and there burnt and reduced to ashes. But with the death of this

body am I dead? Is the body I? It is silent and inert but I feel the full force

of my personality and even the voice of the ‘I’ within me, apart from it. So I

am Spirit transcending the body. The body dies but the Spirit that transcends it

cannot be touched by death. That means I am the deathless Spirit.” All this was

not dull thought; it flashed through me vividly as living truth which I

perceived directly, almost without thought-process. “I” was something very real,

the only real thing about my present state, and all the conscious activity

connected with my body was centered on that “I”. From that moment onwards the

“I” or Self focussed attention on itself by a powerful fascination. Fear of

death had vanished once and for all. Absorption in the Self continued unbroken

from that time on."

What the Amygdala Fears Most

What does this story have to do with the amygdala? The connection lies in

answering a fundamental question: What does the amygdala fear above all else?

The answer is simple: death.

The amygdala, an ancient structure in our brain inherited from the earliest

mammals, operates as a vigilant sentry, constantly scanning the environment with

one wordless query: "Does this situation signal danger or safety?"

If the answer is safety, the amygdala relaxes. But if it detects danger—whether

through sensory input or imagination—it triggers one of two primal responses:

fight or flight. Interestingly, the amygdala doesn’t differentiate between real

and imagined threats. A vividly conjured scenario of danger can elicit the same

physiological response as a tangible tiger lurking in the jungle.

However, the amygdala has a third mode of operation, often overlooked: the

freeze mode—or what could be described as a death simulation. This ancient

response, likely an evolutionary strategy, involves entering a stillness that

mimics death, potentially deterring predators and/or conserving energy during

moments of extreme threat.

Meditation and the Amygdalian Freeze Mode

Here’s where the connection becomes fascinating: true, radical meditation is

deeply intertwined with this freeze response.

In nearly all meditative practices, stillness is paramount. Whether sitting or

lying down, practitioners are instructed to remain utterly immobile, refraining

from even the smallest movements. In Zen, this principle is taken to an extreme,

with monks sitting in unyielding stillness for hours on end.

This meditative stillness mirrors the amygdala’s freeze mode. By simulating this

ancient biological response, meditation places us in a state that transcends the

habitual fear-driven cycles of the amygdala. It interrupts the incessant

fight-or-flight programming, inviting a deeper awareness that lies beyond the

instinctive fear of death.

Connecting the Dots

There is a deep relationship between our biological instincts and spiritual

practices. Through meditation, we come face-to-face with what the amygdala fears

most: stillness, vulnerability, and the symbolic death of the self. Yet, it is

in this stillness—this death of the old reactive self—that a new awareness can

emerge.

I have observed a common trait among those I consider truly spiritual. The

first is their ability to laugh—deeply, genuinely, and often uncontrollably. The

second hallmark, and the one most relevant here, is their intensity. Spiritual

individuals often radiate a profound and constant intensity, yet they

simultaneously exude an inner calm.

Through the lens of my life experience, this intensity is not innate; it is

inherited—from trauma.

From Trauma to Transcendence

For individuals with PTSD, this intensity manifests as an unrelenting state of

hypervigilance—a constant alertness that is both draining and distressing. It’s

as though their internal systems are locked in perpetual survival mode. At the

same time, this heightened state often leads to the suppression of higher brain

functions. Memory, problem-solving, and the ability to utilize full mental

capacity tend to diminish, as these resources are redirected to manage immediate

perceived threats. In psychology, this phenomenon is referred to as regression.

However, for those who have confronted, embraced, and transformed their

trauma—those who have, in a sense, “died into” their pain and emerged

renewed—the story takes a profoundly different turn.

These individuals retain that same intensity, but it is transmuted into a source

of liberated energy. No longer fueling fear or distress, this energy now

contributes to a heightened state of awareness and vitality. The very amygdalian

energy that once perpetuated hypervigilance and survival-driven responses is now

redirected toward higher cognitive and spiritual functions. It provides the

“current” necessary for the mind to shine brighter, for insights to deepen, and

for spiritual presence to expand.

In this way, the energy of the amygdala shifts from a negative force to a

positive one, yet retains its raw intensity. One might say the energy has

transitioned from minus to plus while maintaining its numeric value—a potent

force that, when transformed, becomes a beacon for growth, wisdom, and spiritual

awakening.

This transformation is a testament to the human capacity not just to endure

suffering, but to convert it into a source of strength and consciousness—a kind

of alchemical process that turns trauma into transcendence.

Thus, the biological fear response becomes a gateway to transcendence, but only

when paired with meditative stillness.

What Dying into Pain can Look Like

What does it actually mean to "die

into" one’s trauma? Ramana Maharshi’s experience as a boy offers one profound

clue. However, the process doesn’t always need to be so radical and permanent as

in his case. Sometimes, a glimpse can serve the same purpose. To illustrate, I

invite you to step inside my own story.

As mentioned earlier in the chapter about

Papaji, my father was a wonderful but deeply traumatized man. His childhood

as a sensitive boy in wartime Germany during the Second World War left scars

that shaped his life. Additionally, being born out of wedlock in the 1920s—a

source of great social stigma at the time—was something he perceived as a deep

shame. As someone he loved dearly, I often became the recipient of his

unprocessed shame and anxiety.

An interesting characteristic of trauma is its tendency to pass down through

generations, but often not directly from a grandparent to their grandchildren.

This might be linked to an ancient survival mechanism embedded in the amygdala.

In times of great danger, a high-alert mode in immediate offspring might have

increased their chances of survival. In my case, my father’s stress often

surfaced as anger. When I was a boy, he would shout at me during moments of his

own overwhelm.

Although I grew up surrounded by much love, I carried within me a lingering

sense of unworthiness. Instead of finding peace within myself, I developed a

habit of harsh self-judgment, as if constantly viewing myself through the

critical eyes of others. This "curse," referenced in the Bible as the "sins of

the forefathers," became paradoxically the very gift that brought me to

meditation.

One day, when I was 23 years old, I closed

my eyes for the first time in meditation… and something extraordinary happened.

I died within myself, transfixed in complete stillness. My body became as

immovable as a corpse. In that profound moment, I let go of the self I had

always thought I was—the one shaped by shame, judgment, and unworthiness. What

emerged from that silence was not the person I had been, but someone deeply

connected to an inner stillness, a deeper truth. Though this wonderful

realization eventually faded, it marked the beginning of my spiritual journey.

Unlike Ramana Maharshi and other realized souls who disengaged from the world

and body to fully embrace their enlightenment, my path took a very different

turn. A while after this experience I somehow lost the contact with it and

became deeply entangled with the world—navigating distressed relationships with

women and building a career as a high school teacher, a role I excelled at but

secretly disliked. Despite these external successes, the inner journey remained

ongoing, gradual, and intertwined with the messiness of life. In my case it was

a constant pendulum between having deep insights and then forgetting them in the

engagement with the world.

What is my takeaway from this? I believe that for those who fully disengage from

worldly attachments, enlightenment may arrive suddenly, like a bolt of

lightning. Here it does not matter if the body is a battlefield of trauma. But

for those who, for whatever reason, choose to stay immersed in the complexities

of the world and the body, the spirit enters more gradually. It takes a

lifetime—a slow unfolding. Yet, this gradual process has its own beauty: each

day becomes microscopically better than the last, a subtle but steady movement

toward wholeness and light.

Let me share an example of how a small ray of

light can pierce through the battlefield of the body.

The Angry Teenager

About 25 years ago, I was teaching a music class for teenagers. While

accompanying the class in a collective song on the piano, I noticed a girl

sitting quietly, staring ahead with a serious expression. She wasn’t

participating in the singing. In the chaos of managing the class and trying to

keep everyone engaged, I made a grave mistake. I stopped playing the piano and

teased her, playfully accompanying my words with a line from Monty Python’s

famous song, “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.”

What happened next stunned me. The girl looked at me, her face full of anger,

and shouted, “Die, you pig!” before storming out of the classroom.

The incident quickly escalated. Her parents called the school’s headmaster to

lodge a formal complaint and later called me directly, their voices filled with

anger. The situation spiraled into a significant issue, leaving me overwhelmed

with worry. That night, I went to bed dreading the next day’s challenges. Sleep

eluded me as my body churned with turmoil, fear, and pain. My thoughts raced in

a downward spiral, feeding my anxiety.

Amid this storm of emotions and loud mental chatter, a tiny voice emerged—quiet,

almost imperceptible. It wasn’t a voice made of words but a whisper of

intuition. It said only one thing: surrender.

Deciding to follow this faint inner guidance, I laid flat on my back, completely

still. It was an excruciating position, one I instinctively resisted; I

desperately wanted to curl up on my side instead. Yet, I stayed immobile. I have

no clear memory of how long I remained in that painful stillness.

Then, suddenly, everything shifted. It felt as if a great cathedral of peace

entered my body. The pain that had gripped me moments before was replaced by a

profound bliss, so expansive it felt as though my body dissolved into it. My

entire being became like a tiny droplet suspended within this vast space of

peace. After some time in this state of bliss, I drifted into a deep,

restorative sleep.

The next morning, I woke up fully rested, my mind calm and clear. When I arrived

at work, I was astonished to discover that the crisis had entirely resolved

itself. The girl’s parents had withdrawn their complaint, and even more

surprisingly, the teenage girl approached me with a smile and offered me a

handshake.

After this incident, I gradually became more confident in the art of

surrendering to emotional turmoil—what I now think of as "dying into" it.

Another surprising realization followed: every time I resolved the inner

conflict within myself, the external crisis seemed to dissipate as well.

Whether this connection is magical or simply the result of a calm and centered

mind being better equipped to navigate challenging situations, I leave for you,

dear reader, to explore and decide for yourself.

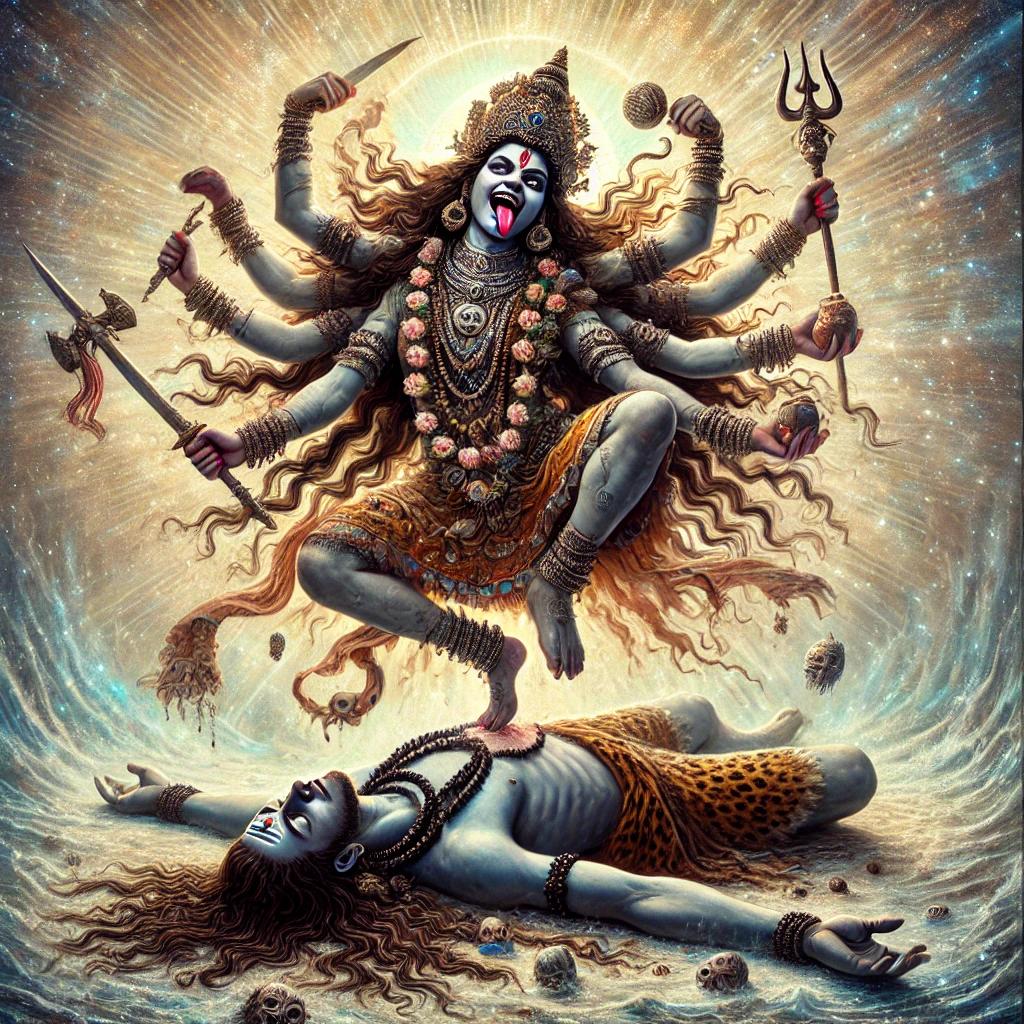

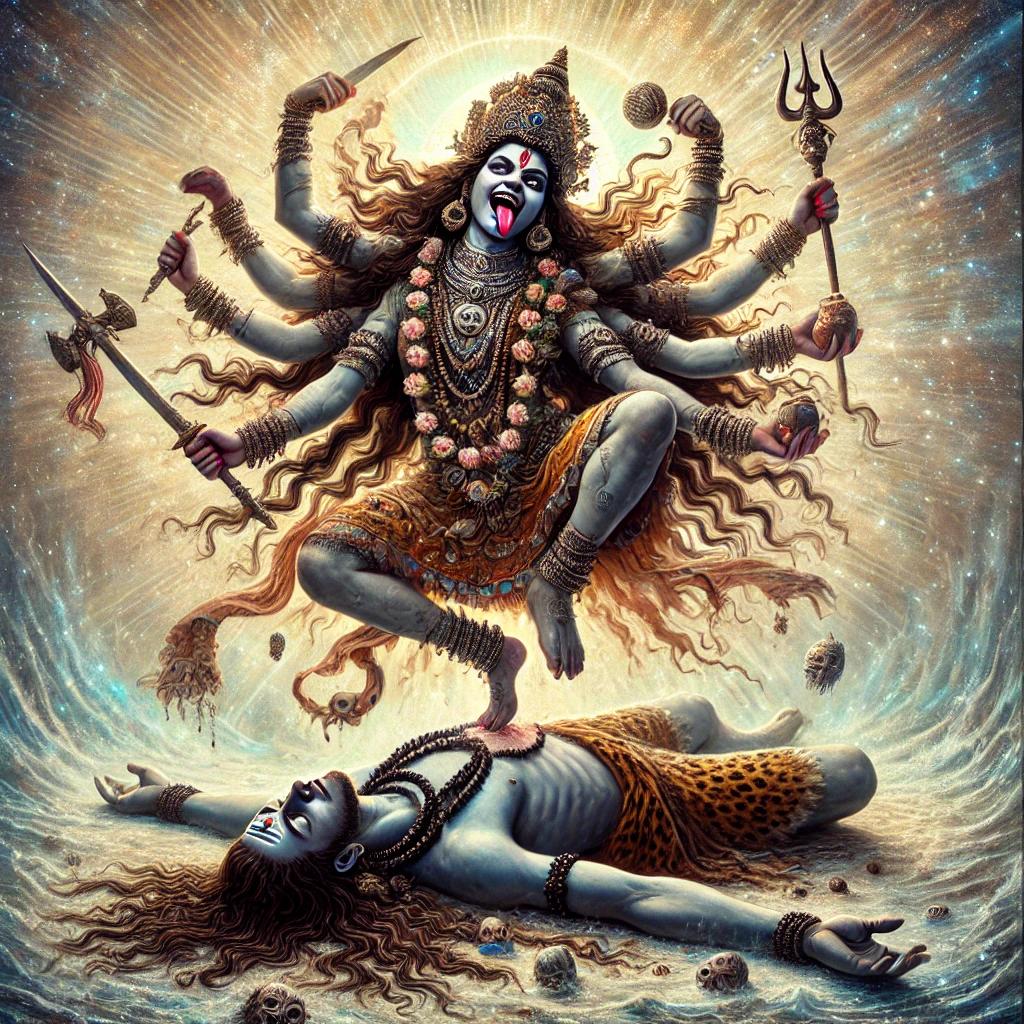

THE DANCE OF KALI

The Indian image of Kali standing on Shiva offers profound symbolism,

particularly when analyzed through the lens of trauma, surrender, and spiritual

transformation.

Kali as the Force of Transformation

Kali, with her fearsome appearance, represents raw, unfiltered

energy—destruction, death, and the untamed force of nature. In the context of

trauma and spirituality, Kali embodies the chaotic upheaval of trauma itself:

the darkness, the fear, and the raw intensity of human suffering. Her severed

heads and blood-red tongue symbolize the cutting away of ego, illusions, and

attachments that keep us bound to pain and fear.

Much like the amygdala’s freeze or death mode, Kali invites us to confront what

we fear most: death, destruction, and the dissolution of the self. Through this

confrontation, she clears the way for renewal and transformation. In her

destruction lies the seed of creation.

Shiva as the Witness and Stillness

Shiva, lying beneath Kali, represents absolute stillness, surrender, and the

unchanging essence of consciousness. He is the symbol of the Self—the eternal,

silent witness that remains untouched by trauma and chaos. His presence beneath

Kali illustrates the interplay between surrender and intensity: the destruction

and chaos of Kali's dance can only unfold on the foundation of Shiva’s immovable

stillness.

This aligns with the theme of "dying into" turmoil. Just as one must surrender

to the pain and chaos of trauma to transcend it, Shiva’s passive, calm surrender

beneath Kali shows the necessity of yielding to higher forces to find

liberation. This interplay reminds us that stillness is not weakness, but the

strength that allows transformation to take place.

Reverse Gender Roles

Traditionally, masculinity is associated with doership and activity, while

femininity is often linked to receptivity and passivity. Interestingly, in this

imagery of Kali and Shiva, these roles are reversed. The male energy, embodied

by Shiva, becomes utterly passive, lying surrendered and immovable, while the

female energy, represented by Kali, is fiercely active, dynamic, and

uncontrollable.

Kali’s wild, unrestrained energy symbolizes the psyche as an extension of the

autonomous nervous system—a force beyond conscious control. This reversal of

roles reminds us that transformation often requires surrendering control,

challenging societal and archetypal norms.

The masculine drive to control cannot meditate. Meditation, in its truest sense,

is a process of non-effort, a state of being in which the ego lets go. Here, it

is Kali—the primal, feminine energy—that meditates us, drawing us into her

transformative dance. This surrender into her energy reveals the deeper truth of

meditation: it is not something we do, but something we allow.

The Dance of Trauma and Transcendence

Kali’s dance on Shiva reflects the paradox of trauma and spirituality. The

external chaos (Kali) may seem overwhelming, but within it lies the opportunity

for profound awakening. Shiva’s stillness suggests that the spirit, when

grounded and unmoving, can endure and transcend even the most intense emotional

upheaval.

Relevance to Meditation and the Amygdala

The stillness of Shiva mirrors the meditative process of entering the

"freeze mode" of the amygdala. By becoming motionless and surrendering to the

moment, the fear-driven cycles of fight or flight are interrupted. This

stillness allows the energy of the "battlefield" (symbolized by Kali's

intensity) to be transmuted into a source of spiritual awakening.

Integration of the Inner and Outer Worlds

The dynamic between Kali and Shiva reflects the principle that inner

resolution often impacts the outer world. When Shiva (inner peace and awareness)

remains steady, Kali’s destructive dance (external turmoil or emotional chaos)

ultimately leads to transformation rather than annihilation. This imagery

reminds us that when we resolve our inner chaos, we often see the crises of the

outer world begin to dissipate.

Together, Kali and Shiva embody the alchemical process of transforming pain and

trauma into spiritual growth. They reveal that the path to transcendence

requires both surrender to chaos and the unyielding stillness to endure it. This

dance is the ultimate balance: the interplay of destruction and creation, fear

and surrender, darkness and light.

With kind regards!

Gunnar Mühlmann

|